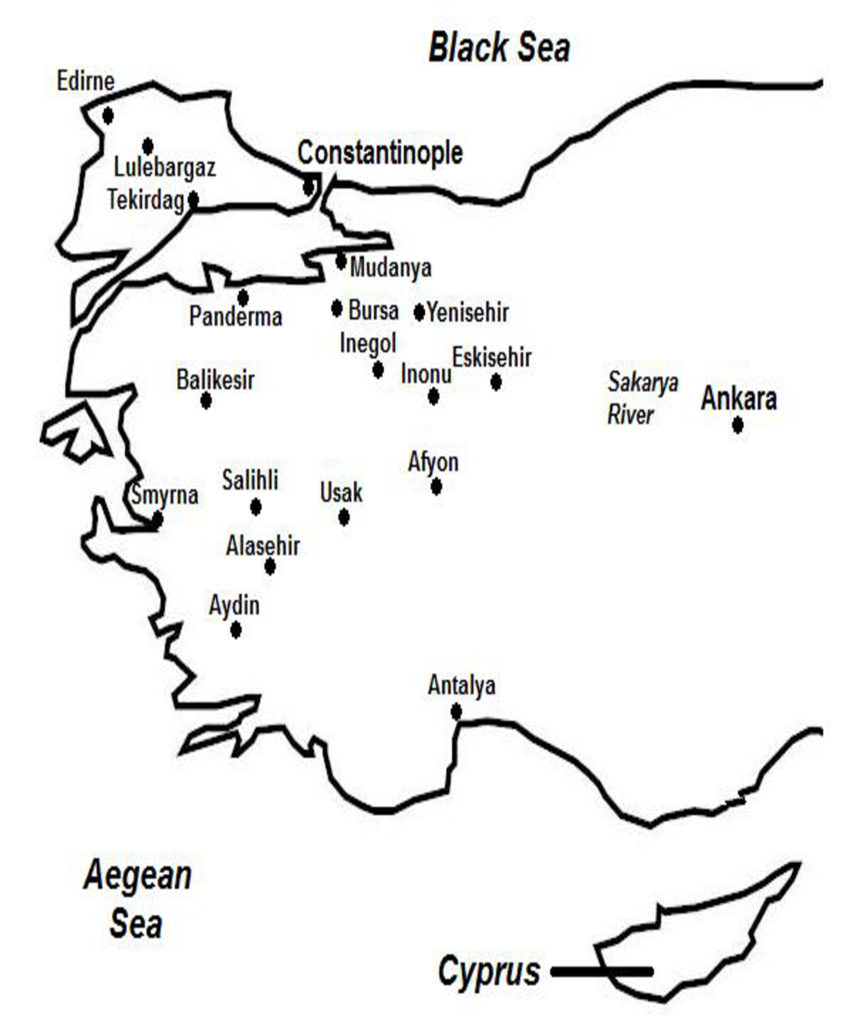

On January 6, 1921, the Greek Army attacked in the direction of the strategic town of Eskişehir, but was repulsed at the First Battle of Inonu. The battle was downplayed by the Greeks as a minor setback, but it considerably raised the morale of the Turks, who for the first time, had turned back the enemy. Because of this development, the Allied Powers (Britain, France, and Italy) met with representatives of the Ottoman government and Turkish nationalists in London (known as the Conference of London) in February-March 1921 in order to negotiate changes to the Treaty of Sevres, which by this time was impossible to implement. However, the Turkish nationalists were unyielding in their position that Turkey’s territorial integrity was non-negotiable and that the Allies must withdraw. As a result, the conference ended without reaching a settlement.

In early March 1921, with the arrival of reinforcements, the Greeks attacked again, but were defeated at the Second Battle of Inonu, and forced to return to Bursa. The Greeks’ southern advance captured Afyon, but a Turkish attempt to cut the railway line between Afyon and Usak forced the Greeks to meet and contain the threat, and then withdraw to Usak.

(Taken from Turkish War of Independence – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 3)

Western Front Greece had entered World War I on the side of the Allies because of Britain’s promise to reward Greece with a large territorial concession of Ottoman Anatolia at the end of the war. Greece particularly was interested in the Ottoman territories that contained a large ethnic Greek population, notably Smyrna, which had a sizable to perhaps even a majority Greek population and was the Greeks’ cultural and economic center in Anatolia, and Eastern Thrace, as well as the islands of Imbros and Tenedos on the Aegean Sea.

As the Ottoman government had repressed ethnic Greeks in Anatolia during the war, the Allied Powers invoked a stipulation in the Armistice of Mudros to allow Greek forces to occupy Smyrna. The presumption was that despite the Ottoman capitulation, ethnic Greeks continued to be threatened by the Ottomans with massacres and dispossession of properties, which were reported to have taken place extensively during the war.

A post-war complication arose since Britain, France, and Italy previously had signed a treaty (Agreement of St.-Jean-de-Maurienne of April 1917), whereby Smyrna and western Anatolia were to be allocated to the Italians. At the Paris Peace Conference held after the war, both the Italian and Greek delegations lobbied hard for Smyrna; in the end, the other Allied powers (led by Britain) voted in favor of Greece.

Then in the Treaty of Sevres of 1920, Italy was granted southern Anatolia centered in Antalya, while Greece was given western Anatolia around Smyrna (as well as most of Eastern Thrace). The Italians, however, felt that they had received the short end of the deal without Smyrna, a resentment that would influence the outcome of the western front.

On May 16, 1919, with Allied approval, 20,000 Greek soldiers landed in Smyrna, where they were greeted as liberators by a large crowd of ethnic Greeks. A commotion broke out when a Turkish gunman fired at the Greek Army, killing one soldier. The Greek Army then opened fire, triggering a spate of violence across the city. When order later was restored, some 300 Turkish and 100 Greek civilians had been killed; many incidents of lootings, beatings, rapes, and other crimes also took place.

War Of the Allied occupations, the Greek entry in Smyrna greatly provoked the Turks. As a result, many Turkish guerilla groups formed, while it was at this time that Kemal began organizing his revolutionary nationalist government. The western front (more commonly known as the Greco-Turkish War of 1919-1922) began in earnest in mid-1920 (eleven months after the initial Greek landing) as a result of Britain’s attempt to implement the newly released Treaty of Sevres. The treaty was presented to and signed by the Ottoman government, but was not ratified; Ottoman authorities insisted that the treaty must be concurred to also by Kemal, who clearly would not agree to it. In fact, Kemal’s nationalist forces, by this time, were fighting the French in the southern front and were preparing a major offensive against the Armenians in the eastern front.

Furthermore, by the time of the Treaty of Sevres, divisions caused by competing interests had developed among the Allies: France resented Britain’s domineering position; Italy wanted to curb British and French domination and Greek expansionism; and the French-Armenian alliance was faltering.