In December 1962, or twenty months after the failed Bay of Pigs Invasion of Cuba, in an agreement between Cuba and the United States, Fidel Castro freed the Brigade 2506 prisoners and allowed them to return to the United States in exchange for the United States delivering $53 million worth of food and medicines to Cuba. Some 60 wounded and ill prisoners had been returned to the United States a few months earlier, while five were executed in Cuba for past crimes. By December 29, 1962, all surviving prisoners had been returned to the United States.

(Taken from Bay of Pigs Invasion – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 2)

Background The rise to power of Fidel Castro after his victory in the Cuban Revolution (previous article) caused great concern for the United States. Castro formed a government that adopted a socialist state policy and opened diplomatic relations with the Soviet Union and other European communist countries. After the Cuban government seized and nationalized American companies in Cuba, the United States imposed a trade embargo on the Castro regime and subsequently ended all economic and diplomatic relations with the island country.

Then in July 1959, just seven months after the Cuban Revolution, U.S. president Dwight Eisenhower delegated the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) with the task of overthrowing Castro, who had by then gained absolute power as dictator. The CIA devised a number of methods to try and kill the Cuban leader, including the use of guns-for-hire and assassins carrying poison-laced devices. Other schemes to destabilize Cuba also were carried out, including sending infiltrators to conduct terror and sabotage operations in the island, arming and funding anti-Castro insurgent groups that operated especially in the Escambray Mountains, and by being directly involved in attacking and sinking Cuban and foreign merchant vessels in Cuban waters and by launching air attacks in Cuba. These CIA operations ultimately failed to eliminate Castro or permanently destabilize his regime.

In March 1960, the CIA began to plan secretly for the invasion of Cuba, with the full support of the Eisenhower administration and the U.S. Armed Forces. About 1,400 anti-Castro Cuban exiles in Miami were recruited to form the main invasion force, which came to be known as “Brigade 2506” (Brigade 2506 actually consisted of five infantry brigades and one paratrooper brigade). The majority of Brigade 2506 received training in conventional warfare in a U.S. base in Guatemala, while other members took specialized combat instructions in Puerto Rico and various locations in the United States.

The CIA wanted to maintain utmost secrecy in order to conceal the U.S. government’s involvement in the invasion. Through loose talk, however, the plan came to be widely known among the Miami Cubans, which eventually was picked up by the American media and then by the foreign press. On January 10, 1961, a front-page news item in the New York Times read “U.S. helps train anti-Castro Force At Secret Guatemalan Air-Ground Base”. Castro’s intelligence operatives in Latin America also learned of the plan; in October 1960, the Cuban foreign minister presented evidence of the existence of Brigade 2506 at a session of the United Nations General Assembly.

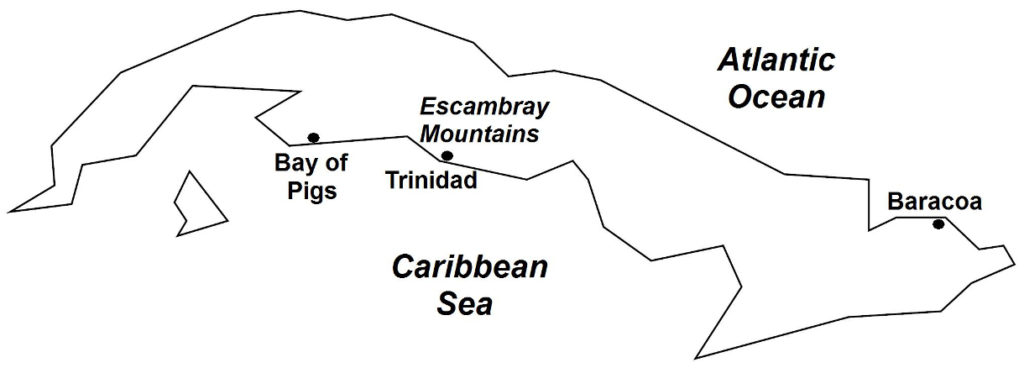

In January 1961, the CIA gave newly elected U.S. president, John F. Kennedy, together with his Cabinet, details of the Cuban invasion plan. The State Department raised a number of objections, particularly with regards to the proposed landing site of Trinidad, which was a heavily populated town in south-central Cuba (Map 30). Trinidad had the benefits of being a defensible landing site and was located adjacent to the Escambray Mountains, where many anti-Castro guerilla groups operated. State officials were concerned, however, that Trinidad’s conspicuous location and large population would make American involvement difficult to conceal.

As a result, the CIA rejected Trinidad, and proposed a new landing site: the Bay of Pigs (Spanish: Bahia de Cochinos), a remote, sparsely inhabited narrow inlet west of Trinidad. President Kennedy then gave his approval, and final preparations for the invasion were made. (The “Cochinos” in Bahia de Cochinos, although translated into English as “pigs” does not refer to swine but to a species of fish, the orange-lined triggerfish, found in the coral waters around the area).

The general premise of the invasion was that most Cubans were discontented with Castro and wanted to see his government deposed. The CIA believed that once Brigade 2506 began the invasion, Cubans would rise up against Castro, and the Cuban Army would defect to the side of the invaders. Other anti-government guerilla groups then would join Brigade 2506 and incite a civil war that ultimately would overthrow Castro. Thereafter, a provisional government, led by Cuban exiles in the United States, would arrive in Cuba and lead the transition to democracy.