On August 9, 1965, the Malaysian parliament voted 126–0 to expel Singapore from Malaysia. Members of Parliament from Singapore were not present during the vote. Later that day, Singapore reluctantly declared its independence; in December 1965, it became the Republic of Singapore.

Singapore’s expulsion was a result of long-simmering tensions, distrust and ideological differences between the federal government in Kuala Lumpur led by the United Malays National Organisation (UMNO) and Singapore’s dominant People’s Action Party (PAP).

Singapore was one of 14 states that formed the country of Malaysia in September 1963 from the merger of the Federation of Malaya with the other former British colonies of Singapore, North Borneo and Sarawak. Singapore’s expulsion in 1963 occurred during the interim period in Malaysia between the Malayan Emergency (1948-1960) and the Second Malayan Emergency (aka Communist Insurgency in Malaysia (1968-1989)).

(Taken from Second Malayan Emergency – Wars of the 20th Century – Twenty Wars in Asia)

After being pushed out of Malaya, the Malay National Liberation Army (MNLA) of the Malayan Communist Party (MCP) established a number of bases in southern Thailand close to the Malayan border, where it began a campaign to recruit new fighters from the local population, both in southern Thailand and northern Malaya. Its ranks soon included some 30% Thai nationals. Also in an effort to widen its support base, the CPM formed the Islamic Brotherhood Party (Malay: Parti Persaudaraan Islam), aimed at attracting ethnic Malays by advocating that Islam and communism were not incompatible ideologies.

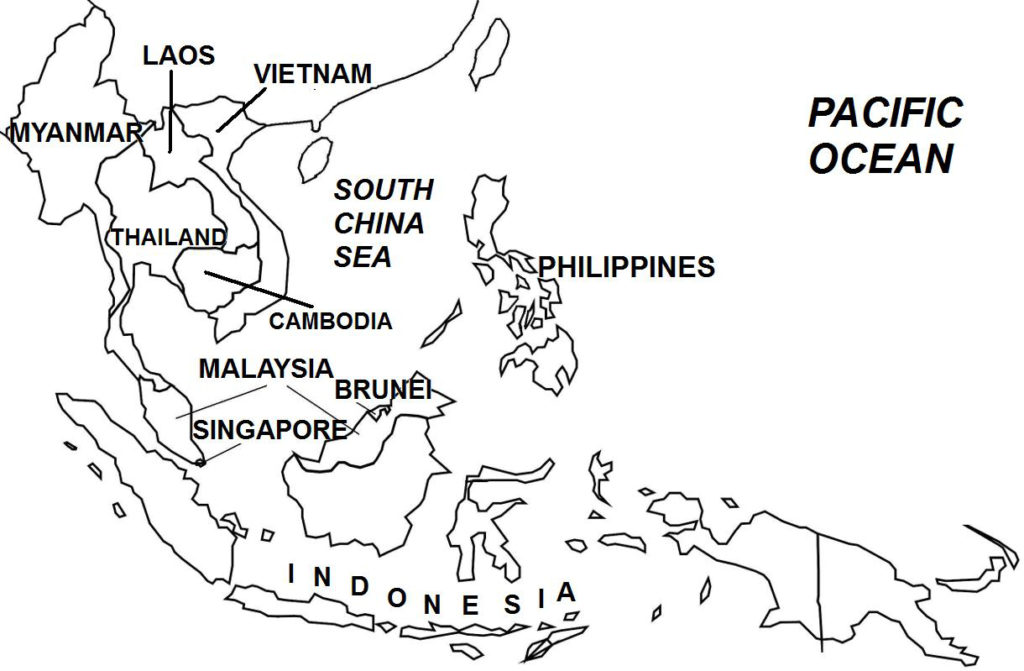

In September 1963, the Federation of Malaya was ended, and replaced by the Federation of Malaysia (or simply Malaysia), consisting of the former Federation of Malaya and the territories of North Borneo (Sabah), Sarawak, and Singapore (in August 1965, Singapore left the Federation and formed a separate independent state).

In the 1960s, with the growth of communist movements in Indo-China (North Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia as well as in Thailand), the CPM stepped up its activities: propaganda and indoctrination campaigns were launched, and recruitment and training accelerated. From some 500-600 fighters remaining by the end of the Emergency, by 1965, the MNLA ranks had increased to some 2,000.

From 1963 to 1966, Malaysia was embroiled in a low-intensity war with neighboring Indonesia. Then by the late 1960s, the Vietnam War was increasing in intensity. In May 1969, racial violence between Malays and Chinese broke out in Malaysia and Singapore, increasing racial tensions and forcing the Malaysian government to impose a state of emergency. Believing that the upsurge in local and regional unrest was playing in its favor, the CPM/MNLA decided to restart hostilities.

This second phase of the war (commonly known as the Communist Insurgency War) began on June 17, 1968 when the MNLA guerillas ambushed Malaysian Army soldiers at Kroh-Betong, in northern Malaysia. Fighting eventually spread to other parts of Peninsular Malaysia, but was much more concentrated in northern Malaysia, and also failed to achieve the degree of intensity and scope experienced during the Malayan Emergency. Furthermore, in 1970, the CPM became wracked in an internal power struggle, which led to the formation of two rival splinter groups, the CPM-Marxist Leninist and CPM-Revolutionary Faction, aside from the original CPM, which continued to have the largest membership. The CPM, which followed the Maoist branch of communism and received support from China, was dealt a major blow when in June 1974, Malaysia and China established diplomatic relations. Although the MNLA tried to maintain military pressure on the Malaysian government, by the early 1980s, the insurgency was experiencing an irrevocable decline.

Much of this decline was a result of the Malaysian government adopting the successful multi-faceted counter-insurgency approach used in the Malayan Emergency, this time carried out in the Security and Development Program (KESBAN, Malay: Keselamatan dan Pembangunan), which consisted of military and civilian measures. Military measures included directly confronting the rebels in combat, utilizing intelligence and psychological operations, and increasing the size and strength of security forces. The civilian component, while also involving resettling villages that were vulnerable to rebel influences and curtailing some civil liberties, focused on a “hearts and minds” approach in the affected communities, e.g. expanding social services and implementing public works programs. Neighborhood Watch and People’s Volunteer Group initiatives not only served security functions in local neighborhoods, but also fostered better interracial relations among Malays, Chinese, and Indians. Furthermore, by the 1980s, Malaysia was experiencing an extended period of dynamic economic growth.

The demise for the CPM also was brought about by the impending end of the Cold War. By 1989, communism was waning globally, communist regimes in Eastern Europe were collapsing, and the Soviet Union itself disintegrated in 1991. In southern Thailand, negotiations between the Malaysian government and CPM (mediated by the Thai government) led to the signing of the Hat Yai Peace Accord (in Hat Yai, Thailand) on December 2, 1989. As stipulated in the agreement, both the CPM and its military wing, the MNLA, were disbanded. The former rebels were allowed to return to Malaysia, an offer that was taken up by some members, while others chose to remain in southern Thailand. The peace agreement did not prohibit Chin Peng, the CPM leader, from returning to Malaysia. However, successive Malaysian governments refused to grant him entry into the country. He passed away in Bangkok, Thailand in September 2013.