On February 3, 1969, Eduardo Mondlane, founder and leader of the Mozambican Liberation Front (FRELIMO), was killed in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, from injuries sustained by a bomb explosion. The bomb was hidden inside a book that had been sent to the FRELIMO headquarters in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania.

In the ensuing power struggle among his followers, FRELIMO’s pro-democracy leaders were expelled and the organization came under the control of Marxists, led by Samora Machel, commander of the rebel forces. Machel adopted a more aggressive approach to the war, increasing the number of rebel fighters, carrying out more guerilla and sabotage operations, and taking the unprecedented step of targeting Portuguese civilians and properties. Under Machel’s leadership, FRELIMO increased its areas of control.

(Taken from Mozambican War of Independence – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 2)

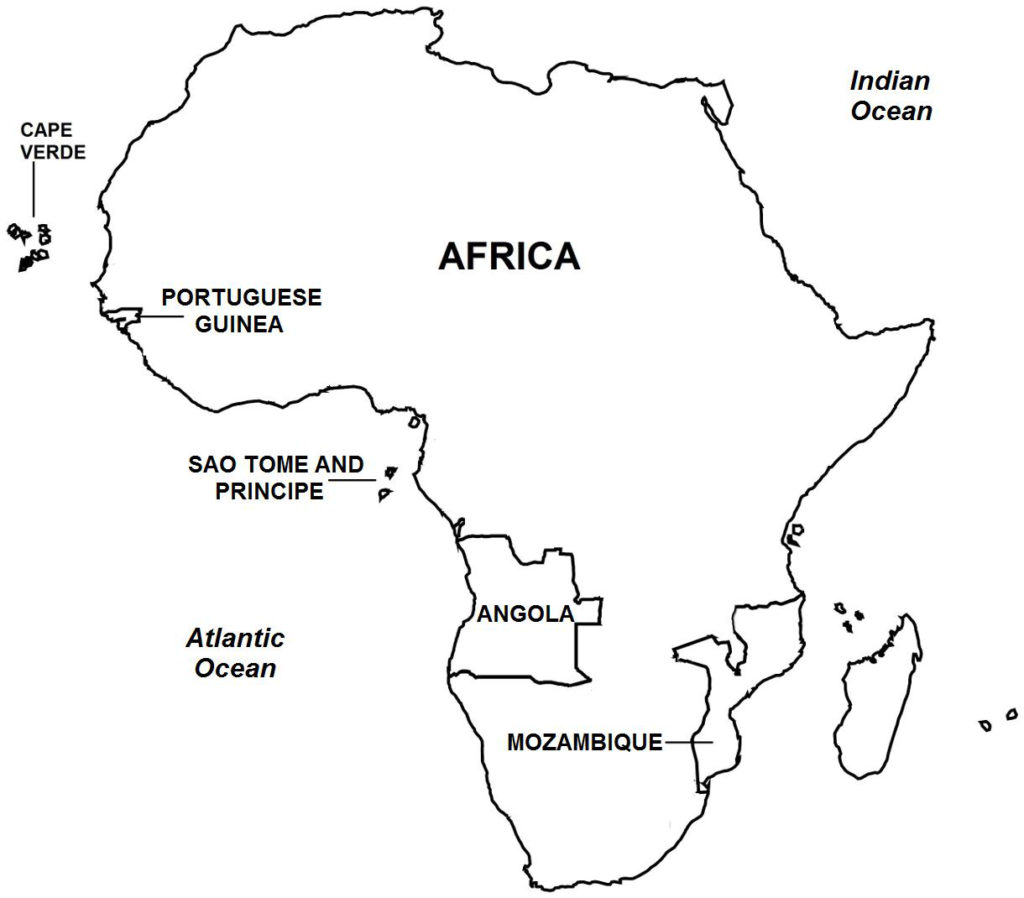

Background After World War II ended in 1945, nationalist aspirations sprung up and spread rapidly across Africa. By the 1960s, most of the continent’s colonies had become independent countries. Portugal, however, was determined to maintain its empire. In 1951, Portugal ceased to regard its African (and Asian) possessions as “colonies”, but integrated them into the motherland as “overseas provinces”. Tens of thousands of Portuguese citizens migrated to Mozambique, as well as to Angola and Portuguese Guinea under the prodding of the national government to lead the development of the new “provinces”.

Because of the immigration, racial tensions, which already were prevalent, escalated in Portugal’s African territories. Portugal took great pride in its official policy of racial inclusiveness, and upheld in its constitution the “democratic, social, and multi-racial” features of Portuguese society. However, the Portuguese Overseas Charter also recognized distinct socio-ethnic classes: citizens – European Portuguese who had full political rights; “assimilados” – black Africans who had assimilated the Portuguese way of life, could read and write, and were eligible to run for local and provincial elected office; and natives – the great majority of black Africans who retained their traditional ways of life.

The Portuguese monopolized the political and economic systems of the colony, while the general population had limited access to education and upward social and economic mobility. By the early 1960s, less than 1% of black Africans had attained “assimilado” status. The colonial government repressed political dissent, forcing many Mozambican nationalists into exile abroad, and used PIDE (Policia Internacional e de Defesa do Estado), Portugal’s security service, to turn Mozambique into a police state.

In June 1962, exiled Mozambican nationalists met in Dar es Salaam, Tanganyika, and merged three ethnic-based independence movements into one nationalist organization, FRELIMO or Mozambique Liberation Front (Portuguese: Frente de Libertação de Moçambique). Led by Eduardo Mondlane, FRELIMO initially sought to gain Mozambique’s independence by negotiating with the Portuguese government. FRELIMO regarded the Portuguese as foreigners who were exploiting Mozambique’s human and natural resources, and were unconcerned with the development and well-being of the indigenous black population.

By 1964, Portugal’s intransigence and the Mozambican colonial government’s repressive acts, including the so-called Mueda Massacre, where security forces opened fire on a crowd of demonstrators, had radicalized FRELIMO into believing that Mozambique’s independence could only be gained through armed struggle. Further motivating FRELIMO into starting a revolution was that Mozambique’s neighbors recently had achieved their independences, i.e. Tanzania in 1961, and Malawi and Zambia in 1964, and these countries’ black-ruled governments would be expected to support Mozambique’s struggle for independence as well.