In the early morning of December 20, 1989, the United States invaded Panama. Approval for the invasion was given on December 17, 1989, which had two major military objectives: to defeat the Panamanian forces and to capture General Noriega. In a nationwide address following the start of the invasion, President Bush gave the following reasons for ordering the invasion: to protect U.S. citizens in Panama, to re-establish democracy and defend human rights in Panama, to combat drug trafficking, and to uphold the Torrijos-Carter Treaties. Some 300 U.S. planes carried out attacks on many targets across Panama, including airfields, army bases, and military-vital public infrastructures.

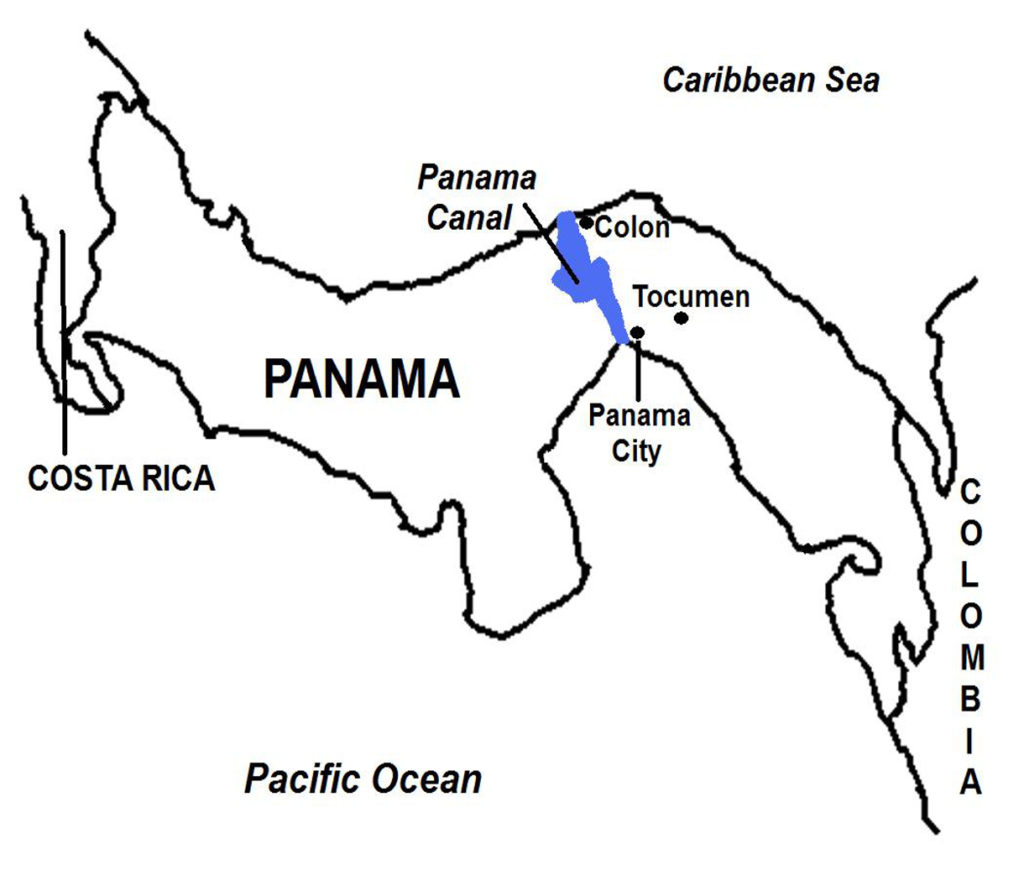

U.S. ground forces, numbering about 28,000 soldiers, advanced from their bases on the Pacific side of the Canal Zone for Panama City, as well as from the Caribbean end of the Canal for Colon. Paratroopers also were airdropped at Tocumen, seizing Torrijos airport. Smaller-scale operations were carried out in Panamanian military and civilian targets in the Canal Zone interior. In Panama City, U.S. air attacks concentrated on the Panamanian Army’s headquarters, which was located in the densely populated neighborhood of El Chorillo. As a result, many civilians were killed and a large fire broke out, burning down the whole neighborhood and leaving thousands of residents without homes.

The Panamanian forces were caught by surprise and failed to mount effective opposition, except for small pockets of resistance. The speed of the U.S. ground offensives also averted prolonged urban combat and thus greater civilian casualties. By December 24, four days into the invasion, large-scale fighting had ended (although skirmishes continued to break out for several weeks more), and General Noriega had taken refuge inside the Apostolic Nunciature (Vatican Embassy) in Panama City. U. S. forces surrounded and blockaded the Embassy’s perimeter but did not enter the building, since doing so to make an arrest was a violation of international law. The Vatican initially was opposed to handing over General Noriega to the United States, as U.S. authorities requested, and instead tried to convince the Panamanian leader to surrender voluntarily.

U.S. authorities exerted diplomatic and psychological pressures, which included tanks rumbling noisily in the streets, helicopters hovering overhead, and 24-hour loud playing of rock music outside the Embassy building. Strong persuasion exerted by Monsignor Jose Sebastian Laboa, the Papal Nuncio (Vatican Ambassador) to Panama, prevailed upon General Noreiga to surrender to the U.S. military on January 3, 1990. Noriega was turned over to the U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) authorities, who transported him to the United States to face trial.

(Taken from United States Invasion of Panama – Wars of the 20th Century – 26 Wars in the Americas and the Caribbean)

Background Since its independence, Panama had been ruled by a succession of civilian governments. In 1968, military officers overthrew the government. General Torrijos, the coup’s leader, established a de facto military regime that ruled behind a façade of a civilian government that was subservient to the military. Then in December 1983, the Panamanian armed forces came under the control of General Manuel Noriega who increased the military’s stranglehold over the country. In general elections held in May 1984, General Noriega manipulated the results of the presidential race to allow his chosen candidate to win.

In the early 1980s, Central America became a major battleground of the Cold War. In search of support, the United States was willing to ignore General Noriega’s abuses of power and have the Panamanian strongman, a staunch anti-communist, as an ally. General Noriega already had a long-standing relationship with the United States, having been an asset and informant of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) since the early 1960s, and had even mediated for the U.S. government with Cuban leader Fidel Castro for the release of American prisoners in Cuba.

General Noriega transformed Panama into a center for smuggling cocaine and other narcotics from Colombia to the United States and other countries. He masterminded and led these operations and later asserted that the CIA and other U.S. government agencies knew and even supported these activities. Meanwhile in the United States, President Ronald Reagan was himself under pressure from an investigation by the U.S. Congress for possible involvement in the “Iran-Contra Affair”, a covert operation where the U.S. government sold weapons to Iran (for the release of American hostages), and the proceeds were then used to fund pro-U.S. “contra” rebels in Nicaragua.

Soon, relations between General Noriega and the U.S. government deteriorated. Then as more reports from Panama indicated General Noriega’s involvement in the drug trade, President Regan put pressure on the Panamanian leader, even urging him to step down from office. President Reagan also was alarmed at the increasing military repression and political instability in Panama, generated by growing opposition to General Noriega’s rule and government corruption. General Noriega particularly was condemned by the local opposition following the murder of Hugo Spadafora, a government critic who had returned to Panama to present evidence of the military leader’s involvement in the drug trade and other crimes. In response to public opposition to his rule, the Panamanian strongman released his forces, resulting in violent confrontations where many civilians were beaten up in street protests.

In February 1988, grand juries in Miami and Florida filed drug smuggling, money laundering, and racketeering lawsuits against General Noriega. Panamanian assets in the United States were frozen, which severely affected Panama that already was reeling as a result of the United States suspension of military aid a year earlier. In March 1988, a coup by security officers failed to overthrow General Noriega. President Reagan also began to explore more forceful ways to depose the Panamanian leader, but preferably to be carried out by Panamanians, and supported or led by the Panamanian military.

In January 1989, George H.W. Bush succeeded as the new U.S. President. By then, the Cold War was drawing to a close – at the end of 1989, Eastern Bloc countries had shed off communism for democracy, while the Soviet Union itself was on the verge of collapse. In Central America, the ongoing Cold War conflicts also were winding down in response to the improving global security and political climates, and the United States felt less the need to continue funding its allies in the region. For the United States, General Noriega’s many faults, which long had been set aside because of his strong anti-communist position, now became too glaring to ignore.

Shortly after taking office, President Bush announced that one of his government’s domestic priorities was to tackle the growing drug problem with a so-called “war on drugs’, aimed at expanding a similar anti-drug campaign that had been in force since the previous administration. A decade earlier, Bush had served as CIA Director (in 1976) and had dealings with Noriega, who was then Panama’s intelligence chief and whose services would become vital for the United States in the heightened Cold War situation in Central America from the late 1970s through most of the 1980s.

Now as U.S. head of state, President Bush sought to distance himself from General Noriega, and made a determined effort to remove the Panamanian leader from power. In May 1989, Panama held general elections. The U.S. government openly supported the main opposition party, hoping that a new government would remove General Noriega as head of the newly created Panama Defense Forces (the Panamanian military and police forces). As election results showed a clear defeat for the government’s hand-picked presidential candidate, General Noriega stopped the tabulations and voided the elections, declaring that meddling by the United States (by supporting the opposition) had undermined the election’s legitimacy. Panama’s electoral tribunal concurred, declaring that widespread fraud had taken place, tarnishing the results. However, international poll observers, which included former U.S. President Carter, concluded that the elections generally were free and fair, and that the opposition’s wide lead in the results genuinely reflected the electorate’s choice. Mass rallies and demonstrations broke out in Panama City; General Noriega responded by sending his paramilitary, called the Dignity Battalion, that attacked and broke up the crowds. In the melee, leading opposition candidates were beaten up, scenes of which were caught by the television news media and aired in the United States. Thereafter, the Organization of American States (OAS) condemned the violence and joined the United States in calling for General Noriega to resign which, however, was rejected by the Panamanian leader.

In October 1989, with partial U.S. support, a group of Panamanian military officers tried to overthrow General Noriega in a coup. Loyal government forces, however, succeeded in rescuing the Panamanian leader, leading to the uprising’s collapse and execution of the coup plotters. In the aftermath, President Bush was criticized for what was perceived as his half-hearted support for the coup.

Meanwhile, as tensions rose between the United States and Panama, the U.S. military sent more troops and weapons to American bases in the Canal Zone. The United States was preparing for a full invasion of Panama, aimed at overthrowing General Noriega. Throughout the summer of 1989, U.S. forces carried out continuous military exercises and maneuvers which Panamanians condemned as a deliberate attempt at provoking an incident to start a war. The increased U.S. military activity so provoked General Noriega that on December 15, 1989, while addressing the Panamanian National Assembly, he declared that a state of war existed between Panama and the United States. At the same gathering, the country’s civilian authority was abolished when the legislators conferred on General Noriega the title of “líder máximo”, or maximum leader, i.e. absolute dictator.

As a result of General Noriega’s actions, President Bush believed that American citizens living in Panama and the Panama Canal were in danger. In the following days, a number of incidents between Panamanian and U.S. forces would precipitate the United States to start the invasion. In one of these incidents, a U.S. Marine was killed when Panamanian security forces manning a roadblock fired on an American vehicle, while another U.S. officer and his wife were arrested, detained, and harassed by Panamanian soldiers.