When French authorities demanded that the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV) government relinquish control of Hanoi, on December 19, 1946, some 30,000 Viet Minh fighters attacked the French, and attempted to block access to the main French garrison in the city. French authorities, who were informed of the plan, foiled the Viet Minh. But the latter detonated explosives that shut down Hanoi’s power plant, cutting off electricity and plunging the city into darkness.

In the ensuing two-month long Battle of Hanoi, French and Viet Minh forces engaged in intense house-to-house fighting, but French military superiority, especially the use of heavy artillery and air firepower, forced Viet Minh forces to evacuate the city and retreat to their traditional strongholds in the Viet Bac region in the far north. French forces then gained control of Hanoi. By late 1946, the Viet Minh still controlled the areas around Haiphong, Hue, and Nam Dinh, but in March 1947, French operations cleared the roads to these major urban areas.

(Taken from First Indochina War – Wars of the 20th Century – Twenty Wars in Asia)

Early in the war, the Viet Minh suffered from a serious lack of weapons, and thus resorted to guerilla warfare. But they took advantage of Vietnam’s thickly covered jungle mountains for refuge and concealment. Jungles and mountains comprised 40% of Vietnam’s territory, an invaluable asset for the Viet Minh, but also a formidable obstacle which French forces were unable to overcome in the war. Throughout the war, while the French controlled the major urban areas, Viet Minh forces operated in much of the hinterland regions, where they established their influence, and gained the support of the residents in remote villages and settlements.

The French military in Indochina was organized as the French Far-East Expeditionary Corps (CEFEO; French: Corps Expéditionnaire Français en Extrême-Orient). At its peak, CEFEO had a total strength of 200,000 troops, and consisted mostly of pro-French Vietnamese soldiers. Small contingents also were brought in from French territories in Africa, as well as from the French Foreign Legion. Early on, CEFEO suffered from inadequate or obsolete weapons, which nonetheless had more firepower than those used by the Viet Minh.

In October 1947, French authorities launched Operation Lea in Bac Can Province (located near the Chinese border) with three major aims: to stop the flow of weapons from China to the Viet Minh, destroy the Viet Minh organization, and capture the Viet Minh leadership. Some 1,000 French commandos were air-dropped in Viet Minh-held territory, while 15,000 ground troops were tasked to block Viet Minh escape routes. The offensive inflicted some 9,000 Viet Minh casualties, but the French also suffered 1,000 killed and 3,000 wounded; large quantities of Viet Minh stores and equipment also were seized. But Ho Chi Minh and his commanders, as well as the bulk of the Viet Minh, slipped past the French cordon.

A second French offensive (Operation Ceinture) in November 1947 near Thai Nguyen and Tuyen Quang failed to battle the Viet Minh, which again escaped. The Viet Minh implemented the policy of carrying out guerilla attacks in scattered areas in order to over-extend French forces and defeat the French in a protected war of attrition. The French soon experienced dwindling military resources and were unable to launch more large-scale attacks, while the Viet Minh, by late 1947, had grown to some 250,000 fighters, and occupied areas that the French had abandoned.

By 1948, France realized that it could not anymore restore colonial rule in Indochina. French authorities therefore opened talks with former Vietnamese emperor Bao Dai regarding establishing a pro-French Vietnamese state, which would accomplish the political objective of undermining the Viet Minh and its DRV government. Negotiations were successful, with the French government and Bao Dai signing two agreements: the First Hai Long Bay Agreement (December 1947), which stipulated Vietnam’s “independence within the French Union”, and the Second Hai Long Bay Agreement (June 1948), which provided for a clearer stipulation of Vietnam’s independence. In both agreements, France would continue to administer Vietnam’s foreign policy decisions and external security functions. As a result of the two agreements, Bao Dai formed a new government in Saigon. However, within a short period, he abdicated and left Vietnam for Europe in frustration at not being granted genuine political power.

The French renegotiated with Bao Dai, which led to the signing in March 1949 of the Elysee Agreement, which stipulated the formation of the State of Vietnam comprising Tonkin, Annam, and Cochinchina. However, the agreement also allowed France to continue to control Vietnam’s foreign policy and external security functions. Bao Dai then returned to Vietnam and formed a new government. Under French oversight, in July 1949, the “independent” Vietnamese state formed its own armed forces (the Vietnamese National Army), which thereafter fought alongside CEFEO.

During the first years of the war, the major world powers saw the conflict merely as an internal (i.e. colonial) matter of the French, or an independence struggle of the Vietnamese people. In March 1947, U.S. President Truman delivered a speech, which eventually came to be known as the Truman Doctrine, where he vowed to “contain” what he saw was the Soviet Union’s expansionist ambitions in Greece and Turkey. This new American policy marked the start of the Cold War.

During World War II and in the immediate aftermath, the U.S. government appeared opposed to restoring French rule in Indochina, for a number for reasons: Ho Chi Minh had been a U.S. ally in the war; pre-war French colonial rule had been repressive; and the United States was averse to colonialism. But with the restoration of French rule, the United States kept a hands-off policy in Indochina.

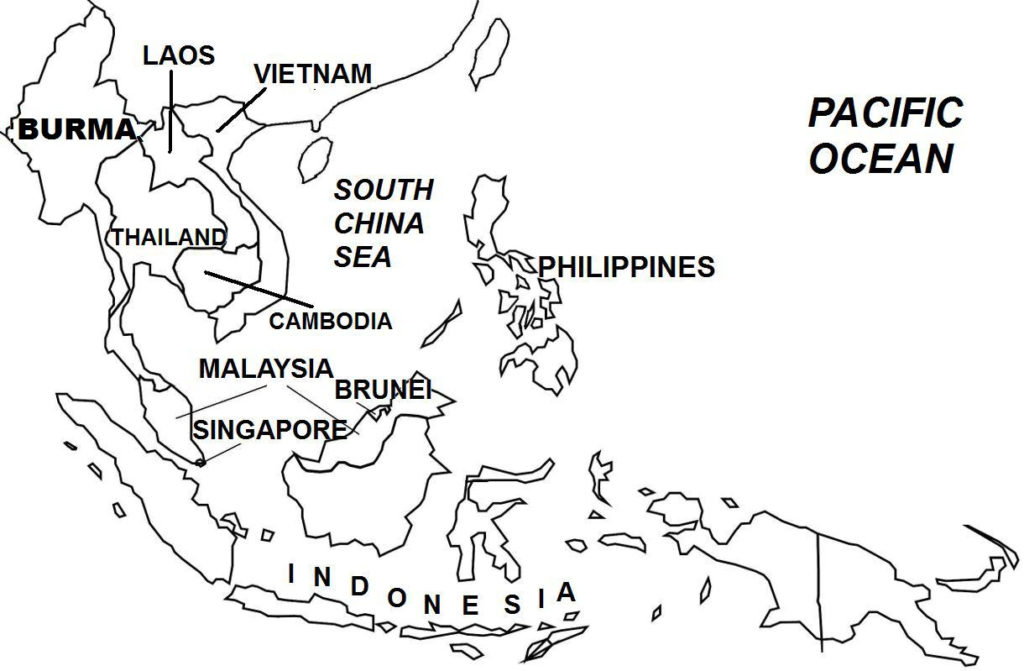

Two events changed U.S. policy toward Indochina and Asia. First, in October 1949, Chinese communists, emerging victorious after a long civil war in China, established the People’s Republic of China (PRC), a communist state. Second, in June 1950, North Korea, backed by the Soviet Union and the PRC, invaded U.S.-allied South Korea, triggering the Korean War. President Truman became convinced that not only did the Soviet Union have expansionist ambitions in Europe, but that Soviet leader Josef Stalin and Chinese leader Mao Zedong also were determined to spread communism in Asia. The next U.S. President, Dwight D. Eisenhower, would introduce the Domino Principle, which stated that if the communists prevailed in Korea and Vietnam, the rest of the countries of Southeast Asia would be next to fall to communism, akin to a row of dominoes falling one after the other.

As a result, the United States strengthened its military presence in East Asia, reversing its post-World War II policy of withdrawing American forces from the region. In February 1950, the U.S. government recognized the French-backed State of Vietnam, which was led by Bao Dai. In July 1950, the first shipments of U.S. war supplies arrived. Three months later (September 1950), after French and American military officials held talks in Washington, D.C., the United States established the Military Assistance and Advisory Group (MAAG), tasked with serving as the liaison agency that would provide weapons, as well as military advice and training. U.S. military support to the French would dramatically increase over the following years to a total of $3 billion. By 1954, the United States would be supplying 80% of the total weapons used by French forces in Vietnam. A total of 1,400 tanks, 340 planes, 240,000 small firearms, and 150 million bullets were sent.