On December 15, 1971, Indian forces entered Dhaka, the capital of East Pakistan, capturing over 90,000 Pakistani soldiers. With the fall of East Pakistan, fighting in the western sector of the Indian-Pakistani War of 1971 ended.

Following the war, India and Pakistan entered into a number of agreements in the hope of resolving their differences. India returned to Pakistan the 90,000 Pakistani prisoners of war, as well as areas in Pakistan that it had captured during the war. In exchange, Pakistan agreed to recognize Bangladesh’s independence. Pakistani authorities then released Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, the jailed Bengali leader, who returned to Bangladesh and subsequently became his country’s first president.

(Taken from Bangladesh War of Independence and Indian-Pakistani War of 1971 – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 3)

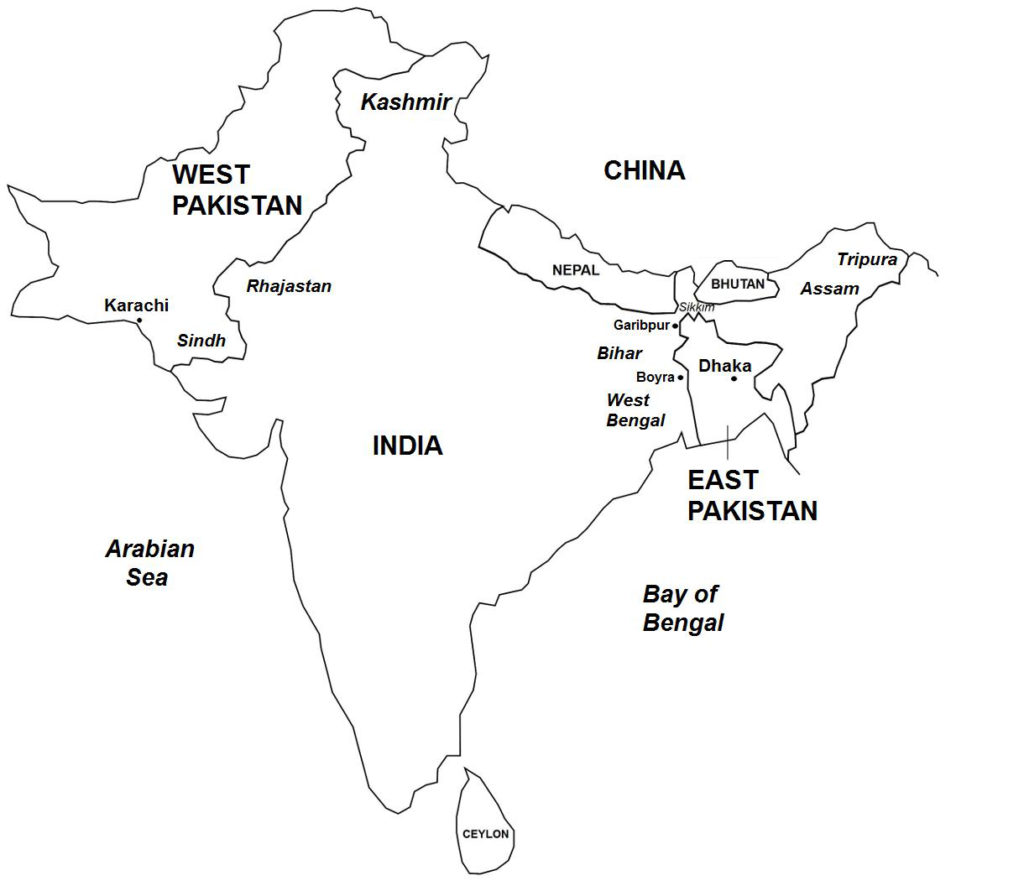

Background In 1947, the Indian subcontinent was partitioned (previous article) into two new countries: the Hindu-majority India and the nearly exclusive Muslim Pakistan. Much of India was formed from the subcontinent’s central and eastern regions, while Pakistan comprised two geographically separate regions that became West Pakistan (located in the northwest) and East Pakistan (located in the southeast).

From its inception, Pakistan experienced a great disparity between West Pakistan and East Pakistan. The national capital was located in West Pakistan, from where all major political and governmental decisions were made. Military and foreign policies emanated from there as well. West Pakistan also held a monopoly on the country’s financial, industrial, and social affairs. Much of the country’s wealth entered, remained in, and was apportioned to the West. These factors resulted in West Pakistan being much wealthier than East Pakistan. And all this despite East Pakistan having a higher population than West Pakistan.

In the 1960s, East Pakistan called for social and economic reforms and greater regional autonomy, but was ignored by the national government. Then in 1970, the Amawi League, East Pakistan’s main political party, won a stunning landslide victory in the national elections, but was prevented from taking over the government by the ruling civilian-military coalition regime, which feared that a new civilian government would reduce the military’s influence on the country’s political affairs.

Leaders from East Pakistan and West Pakistan tried to negotiate a solution to the political impasse, but failed to reach an agreement. Having been prevented from forming a new government, Mujibur Rahman, East Pakistan’s leader, called on East Pakistanis to carry out acts of civil disobedience.

In Dhaka, the East Pakistani capital, thousands of residents undertook mass demonstrations that paralyzed commercial, public, and civilian functions. On March 25, 1971, the Pakistani Army arrested and jailed Mujibur, who then declared while in prison the secession of East Pakistan from Pakistan and the founding of the independent state of Bangladesh. Mujibur’s supporters aired the declaration of independence on broadcast radio throughout East Pakistan.

East Pakistanis then organized the Mukti Bahini, a guerilla militia whose ranks were filled by ethnic Bengali soldiers who had defected from the Pakistani Army. As armed clashes began to break out in Dhaka, the national government sent more troops to East Pakistan. Much of the fighting took place in April-May 1971, where government forces prevailed, forcing the rebels to flee to the Indian states of West Bengal and Tripura. The Pakistani Army then turned on the civilian population to weed out nationalists and rebel supporters. The soldiers targeted all sectors of society – the upper classes of the political, academic, and business elite, as well as the lower classes consisting of urban and rural workers, farmers, and villagers. In the wave of violence and suppression that took place, tens of thousands of East Pakistanis were killed, while some ten million civilians fled to the Indian states of West Bengal, Tripura, Assam, Bihar, and Meghalaya.

As East Pakistani refugees flooded into India, the Indian government called on the United Nations (UN) to intervene, but received no satisfactory response. As nearly 50% of the refugees were Hindus, to the Indian government, this meant that the causes of the unrest in East Pakistan were religious as well as political. (During the partition of the Indian subcontinent in 1947, a massive cross-border migration of Hindus and Muslims had taken place; by the 1970s, however, East Pakistan, still contained a significant 14% Hindu population.)

Since its independence, India had fought two wars against Pakistan and faced the perennial threat of fighting against or being attacked simultaneously from East Pakistan and West Pakistan. India therefore saw that the crisis in East Pakistan yielded one benefit – if the threat from East Pakistan was eliminated, India would not have to face the threat of a war on two fronts. Thus, just two days into the uprising in East Pakistan, India began to secretly support the independence of Bangladesh. The Indian Army covertly trained, armed, and funded the East Pakistani rebels, which within a few months, grew to a force of 100,000 fighters.

In May 1975, India finalized preparations for an invasion of East Pakistan, but moved the date of the operation to later in the year when the Himalayan border passes were inaccessible to a possible attack by the Chinese Army. India had been defeated by China in the 1962 Sino-Indian War, and thus was wary of Chinese intentions, more so since China and Pakistan maintained friendly relations and both considered India their common enemy. As a result, India entered into a defense treaty with the Soviet Union that guaranteed Soviet intervention in case India was attacked by a foreign power.

In late spring and summer of 1971, East Pakistani rebels based in West Bengal entered East Pakistan and carried out guerilla attacks against the Pakistani Army. These infiltration attacks included sabotaging military installations and attacking patrols, outposts, and other lightly defended army positions. Government forces threw back the attacks and sometimes entered into India in pursuit of the rebels.

By October 1971, the Indian Army became involved in the fighting, providing artillery support for rebel infiltrations and even openly engaging the Pakistani Army in medium-scale ground and air battles along the border areas near Garibpur and Boyra (Map 14).