The United Nations offered a proposal for the partition for Palestine which the UN General Assembly subsequently approved on November 29, 1947. The Palestinian Jews accepted the plan, whereas the Palestinian Arabs rejected it. The Palestinian Arabs took issue with what they felt was the unfair division of Palestine in relation to the Arab-Jewish population ratio. The Jews made up 32% of Palestine’s population but would acquire 56% of the land. The Arabs, who comprised 68% of the population, would gain 43% of Palestine. The lands proposed for the Jews, however, had a mixed population composed of 46% Arabs and 54% Jews. The areas of Palestine allocated to the Arabs consisted of 99% Arabs and 1% Jews. No population transfer was proposed. Jerusalem and its surrounding areas, with their mixed population of 100,000 Jews and an equal number of Arabs, were to be administered by the UN.

(Taken from 1947-1948 Civil War in Palestine – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 1)

Background Through a League of Nations mandate, Britain administered Palestine from 1920 to 1948. For nearly all that time, the British rule was plagued by violence between the rival Arabs and Jewish populations that resided in Palestine. The Palestinian Arabs resented the British for allowing the Jews to settle in what the Arabs believed was their ancestral land. The Palestinian Jews also were hostile to the British for limiting and sometimes even preventing other Jews from entering Palestine. The Jews believed that Palestine had been promised to them as the site of their future nation. Arabs and Jews clashed against each other; they also attacked the British authorities. Bombings, massacres, assassinations, and other violent civilian incidents occurred frequently in Palestine.

By the end of World War II in 1945, nationalist aspirations had risen among the Palestinian Arabs and Palestinian Jews. Initially, Britain proposed an independent Palestine consisting of federated states of Arabs and Jews, but later deemed the plan unworkable because of the uninterrupted violence. The British, therefore, referred the issue of Palestine to the United Nations (UN). The British also announced their intention to give up their mandate over Palestine, end all administrative functions there, and withdraw their troops by May 15, 1948. The last British troops actually left on June 30, 1948.

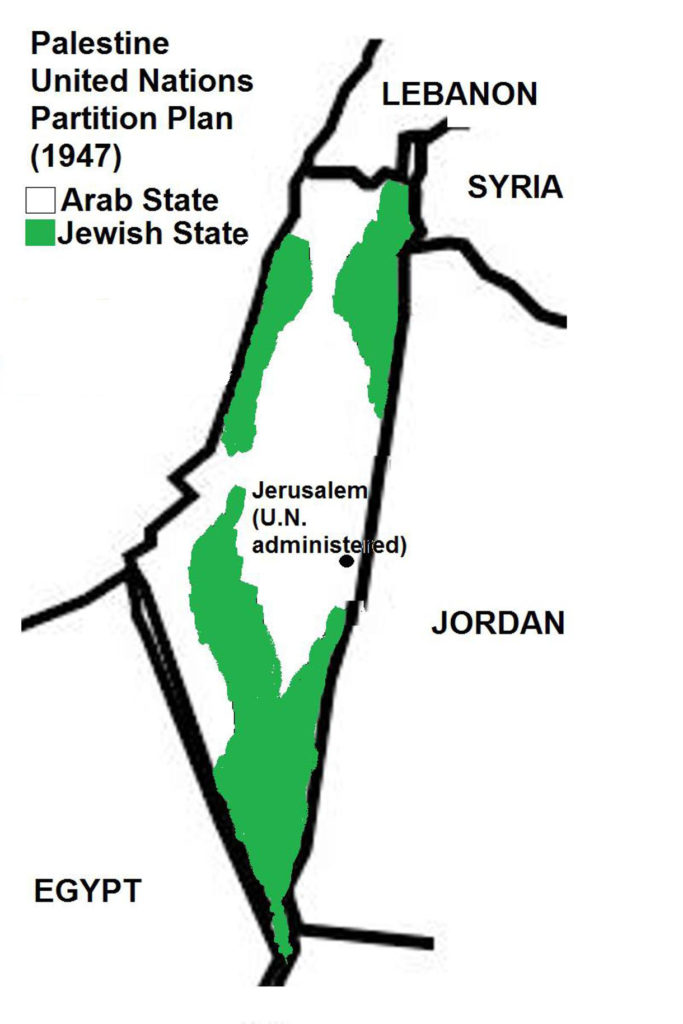

The UN offered a proposal for the partition for Palestine (Map 8) which the UN General Assembly subsequently approved on November 29, 1947. The Palestinian Jews accepted the plan, whereas the Palestinian Arabs rejected it. The Palestinian Arabs took issue with what they felt was the unfair division of Palestine in relation to the Arab-Jewish population ratio. The Jews made up 32% of Palestine’s population but would acquire 56% of the land. The Arabs, who comprised 68% of the population, would gain 43% of Palestine. The lands proposed for the Jews, however, had a mixed population composed of 46% Arabs and 54% Jews. The areas of Palestine allocated to the Arabs consisted of 99% Arabs and 1% Jews. No population transfer was proposed. Jerusalem and its surrounding areas, with their mixed population of 100,000 Jews and an equal number of Arabs, were to be administered by the UN.

1947-1948 Civil War in Palestine Shortly after the UN approved the partition plan, hostilities broke out in Palestine. Armed bands of Jews and Arabs attacked rival villages and settlements, threw explosives into crowded streets, and ambushed or used land mines against vehicles plying the roads. Attacks and punitive attacks occurred; single gunfire shots led to widespread armed clashes.

By the end of May 1948, over 2,000 Palestinian civilians (Arabs and Jews) had been killed and thousands more had been wounded. The British still held legal authority over Palestine, but did little to stop the violence, as they were in the process of withdrawing their forces and disengaging from further involvement in the region’s internal affairs. The British did interfere in a few instances and suffered casualties as well.

A large Jewish paramilitary, as well as a number of smaller Jewish militias, already existed and operated clandestinely during the period of the British mandate. As the violence escalated, Jewish leaders integrated these armed groups into a single Jewish Army.

Fighting on the side of the Palestinian Arabs were two rival armed groups: a smaller militia composed of Palestinian Arab fighters, and a larger paramilitary organized by the neighboring Arab countries. Egypt, Syria, and Jordan did not want to send their armies to Palestine at this time since this would be an act of war against powerful Britain.

During the course of the war, the Jews experienced major logistical problems with the distant Jewish settlements that were separated from the main Jewish strongholds along the coast. These Jewish exclaves included Jerusalem, where one-sixth of all Palestinian Jews lived, as well as the many small villages and settlements in the north (Galilee) and in the south (Negev).

Jewish leaders sent militia units to these areas to augment existing local defense forces that consisted solely of local civilians. These isolated settlements were instructed to hold their ground at all costs. Supplying these Jewish exclaves was particularly dangerous, as delivery convoys were ambushed and had to traverse many Arab settlements along the way. Food rationing, therefore, was imposed in many distant Jewish settlements, a policy that persisted until the war’s end.

The Jews gained a clear advantage in the fighting after they had organized a unified army. Their military leaders imposed mandatory conscription of men and single women, first only for the younger adult age groups, and later, for all men under age 40 and single women up to age 35. By April 1948, the Jewish Army had numbered 21,000 soldiers, up significantly from the few thousands at the start of the war.

The Jews also increased their weapons stockpiles from generous contributions made by wealthy donors in Europe and the United States. As the UN had imposed an arms embargo on Palestine, the Jews smuggled in their weapons, which were purchased mainly from dealers in Czechoslovakia. These weapons began to arrive in Palestine early in the fighting, greatly enhancing the Jews’ war effort. The Jews also procured some weapons from clandestine small-arms manufacturers in Palestine; however, the output from local manufacturers was insufficient to fill the demands of the Jews’ growing army as well as the widening conflict.

Starting in April 1948, the Jewish Army launched a number of offensives aimed at securing Jewish territories as well as protecting Jewish civilians in Arab-held areas. These Jewish operations were carried out in anticipation of the Arab armies intervening in Palestine once the British Mandate ended on May 15, 1948.

On April 2, 1948, Jewish forces advanced toward Jerusalem in order to lift the siege on the city and allow the entry of supply vehicles. The Jews cleared the roads of Arab fighters and took control of the Arab villages nearby. The operation was only partially successful, however, as Jewish delivery convoys continued to be ambushed along the roads. Furthermore, Jewish authorities were condemned by the international community after a Jewish attack on the Arab village of Deir Yassin resulted in the deaths of over one hundred Arab civilians.

On April 8, Jewish forces succeeded in lifting the siege on Mishmar Haemek, a Jewish kibbutz in the Jezreel Valley. The Jews then launched a counter-attack that captured nearby Arab settlements. Further offensives allowed the Jews to seize control of northeastern Palestine. Also falling to Jewish forces were Tiberias in mid-April, Haifa and Jaffa later in the month, and Beisan and Safed in May. In southern Palestine, the Jews captured key areas in the Negev. The Jewish offensives greatly reduced the Palestinian Arabs’ capacity to continue the war.

In the wake of the Jewish victories, hundreds of thousands of Arab civilians fled from their homes, leaving scores of empty villages that were looted and destroyed by Jewish forces. Earlier in 1948, tens of thousands of middle-class and upper-class Arabs had left Palestine for safety in neighboring Arab countries. Jewish authorities formally annexed captured Arab lands, merging them with Jewish territories already under their control.

On May 14, 1948, one day before the end of the British Mandate in Palestine, the Jews declared independence as the State of Israel. The following day, British rule in Palestine ended. Within a few hours, the armies of the Arab countries, specifically those from Egypt, Jordan, Syria, Lebanon, and Iraq, invaded the new country of Israel, triggering the second phase of the conflict – the 1948 Arab-Israeli War (next article).