In July 1966, Prince Ndizeye of Burundi claimed the throne, designating himself King Ntare V, and appointed Michel Micombero, the Defense Minister, as the country’s Prime Minister. But on November 28, 1966, Micombero overthrew King Ntare, abolished the monarchy, and declared the country a republic with himself as its first president.

The fall of the Burundian monarchy marked the end of a moderating middle force against the hostility between the country’s two main ethnic groups: Hutus and Tutsis. President Micombero ruled as a military dictator, despite the country being officially a democracy; he consolidated power by repressing all opposition, particularly the militant Hutu factions. Many moderate Hutus continued to serve in the civil service and even top government bureaucracy, but only in positions subordinate to Tutsis.

(Taken from Burundi’s Inter-ethnic Strife – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 2)

After World War II ended in 1945, nationalist sentiments emerged and expanded rapidly within the African colonies. To prepare Burundi for independence, in November 1959, Belgium allowed political parties to organize. Then in parliamentary elections held in September 1961, UPRONA or Union for National Progress (French: Union pour le Progres National), which comprised Tutsi and Hutu politicians, won a clear majority in the legislature. Prince Louis Rwagasore, UPRONA leader and the king’s son, became prime minister. Just one month later, however, Prince Rwagasore was assassinated, ending his vision of integrating Burundi’s ethnic classes. Prince Rwagasore’s death also led to a period of successive Tutsi and Hutu political leaders alternating as prime minister.

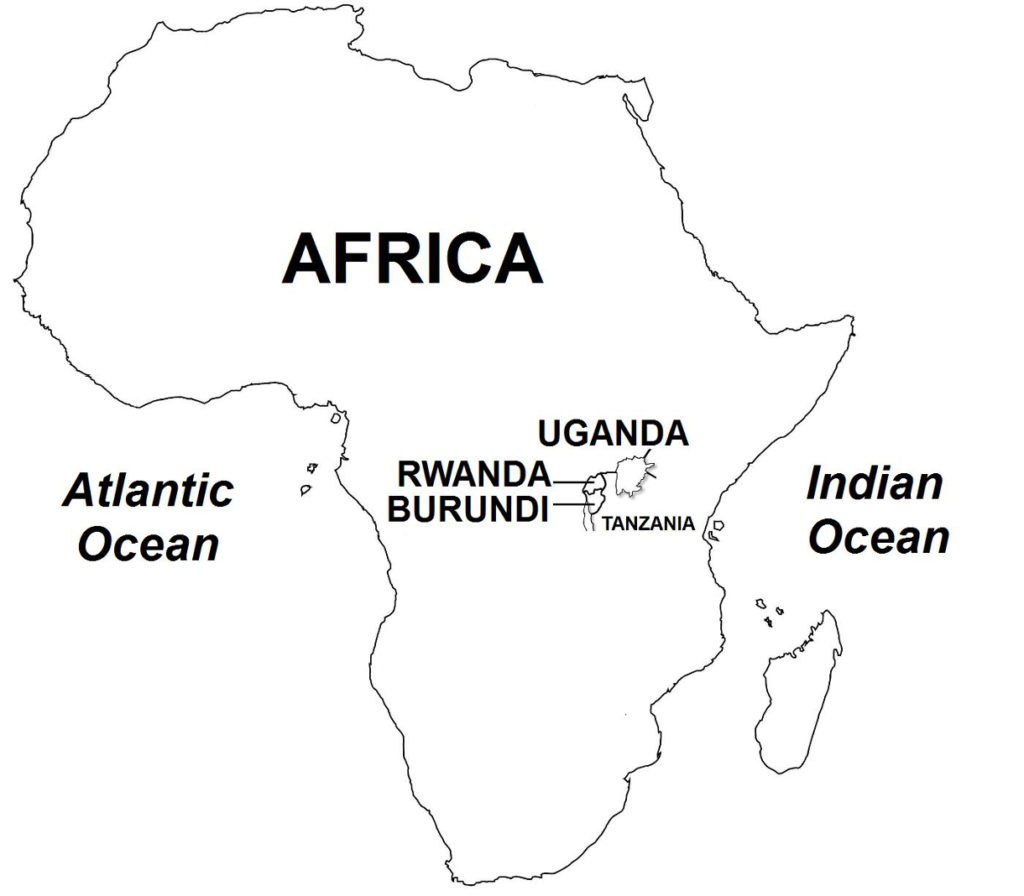

On June 20, 1962, Ruanda-Urundi ceased as a United Nations Trust Territory under Belgian administration and the colony’s union was dissolved. Then on July 1, 1962, Urundi, renamed Burundi, and Ruanda, renamed Rwanda, both gained their independences. Burundi was established as a constitutional monarchy, with the monarch, then King Mwambutsa IV, as ceremonial head of state, and governmental powers vested in a Prime Minister and a national legislature. The Parliament was controlled by the bi-ethnic UPRONA, but by 1963, serious rifts in the party had developed along ethnic lines. In January 1965, the Prime Minister, a Hutu, was assassinated, which triggered a flurry of ethnic violence with Hutus attacking Tutsis, and retaliations by the Tutsi-dominated military forces targeting Hutus. In the elections held in May of that year, Hutu politicians gained control of Parliament and then elected another Hutu as Prime Minister. King Mwambutsa, already overwhelmed by the rising tensions, rejected the selection and named a Tutsi as Prime Minister.

In October 1965, Hutu military officers attempted to depose the monarch in a coup, but failed. Violent reprisals by government forces followed, which claimed the lives of some 5,000 Hutu military officers and top government officials. The purge of influential Hutus allowed the Tutsis to gain political and military control and achieve a monopoly over state power that would last for many years.

The ethnic unrest also was a result of the much greater turmoil that had erupted in Rwanda, Burundi’s northern neighbor that likewise shared a similar ethnic composition of Hutu, Tutsi, and Twa populations and where in 1959, Hutus broke out in riots and killed tens of thousands of Tutsis, seized power by deposing the Tutsi monarchy, and established a Hutu one-party state (previous article). Some 150,000 Rwandan Tutsis fled into exile in neighboring countries, including Burundi. In the ensuing years, the events that were transpiring in Rwanda would have repercussions in Burundi, and vice-versa.

In Burundi, as a result of the coup attempt, King Mwambutsa went into exile abroad in November 1965; soon thereafter, he handed over all royal duties to his son, Prince Ndizeye. In July 1966, Prince Ndizeye claimed the throne, designating himself King Ntare V, and appointed Michel Micombero, the Defense Minister, as the country’s Prime Minister. In November 1966, Micombero overthrew King Ntare, abolished the monarchy, and declared the country a republic with himself as its first president.

The fall of the Burundian monarchy marked the end of a moderating middle force against the hostility between Hutus and Tutsis. President Micombero ruled as a military dictator, despite the country being officially a democracy; he consolidated power by repressing all opposition, particularly the militant Hutu factions. Many moderate Hutus continued to serve in the civil service and even top government bureaucracy, but only in positions subordinate to Tutsis.

In 1971, President Micombero faced a different challenge, this time in northern Burundi from the Banyaruguru, a Tutsi subgroup, whom he believed were planning to overthrow the government (Micombero’s government was dominated by Tutsi-Hima, another Tutsi subgroup, from southern Burundi). Consequently, nine Tutsi-Banyaruguru government officials and military officers were executed while others received jail sentences.

Then in April 1972, Hutus in southern Burundi, taking advantage of the intra-ethnic Tutsi turmoil, rose up in revolt. The uprising, which also was triggered by the government’s repressive policies and additional purges of Hutu military officers, began in Bururi Province, particularly in Rumonge, and spread quickly to other areas around Lake Tanganyika, where machete- and spear-wielding bands of Hutu fanatical youths roamed the countryside, attacked Tutsi villages, raided police and military stations, and destroyed public infrastructures. Within a few days, some 1,000 to 3,000 Tutsis had been killed before the marauders, now armed with firearms seized from government armories, withdrew to Vyanda where they proclaimed independence as the “Martyazo Republic”.

The government’s response was swift and brutal, with the military forces crushing the rebellion and declaring that the rebels were communists. Furthermore, Micombero, who was from Bururi Province, was determined to end the Hutu threat once and for all. As a consequence of the rebellion, many Hutu government officials and military personnel were executed. Recruitment to the armed forces was amended to virtually exclude Hutus and only allow Tutsis.

Hutu students of all ages, and Hutu teachers were rounded up from the schools and later transported to designated areas where they were executed. Government soldiers, as well as their Tutsi paramilitary allies, carried out the executions, including those of the Hutu clergy and influential Hutu members of society. From late April to September 1972, some 100,000 to 200,000 Hutus were killed in the event known as the 1972 Burundi Genocide. An estimated 10,000 Tutsis also lost their lives during the period. Some 300,000 Hutus also fled as refugees to neighboring Rwanda, Zaire, and particularly in Tanzania.