On November 16, 1912, Serbian forces pushed into Bitola, starting an intense three-day battle during the First Balkan War. The Ottomans were defeated, and forced to abandon the whole the province and retreat to the Berat region in central Albania, as well as to the fortress city of Ioannina, which was then under siege by the Greek Army.

The Serbians then advanced toward Albania, taking most of the region north of Vlora and into the Adriatic Coast, thereby achieving Serbia’s ambition of gaining access to the Mediterranean Sea. Montenegrin forces also occupied a section of northern Albania, and advanced to the fortified city of Shkoder, where they began a siege on October 28, 1912 that would last for several months.

(Taken from First Balkan War – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 3)

Background At the start of the twentieth century, the Ottoman Empire was a spent force, a shadow of its former power of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries that had struck fear in Europe. The empire did continue to hold vast territories, but only tolerated by competing interests among the European powers who wanted to maintain a balance of power in Europe. In particular, Britain and France supported and sometimes intervened on the side of the Ottomans in order to restrain expansionist ambitions of the emerging giant, the Russian Empire.

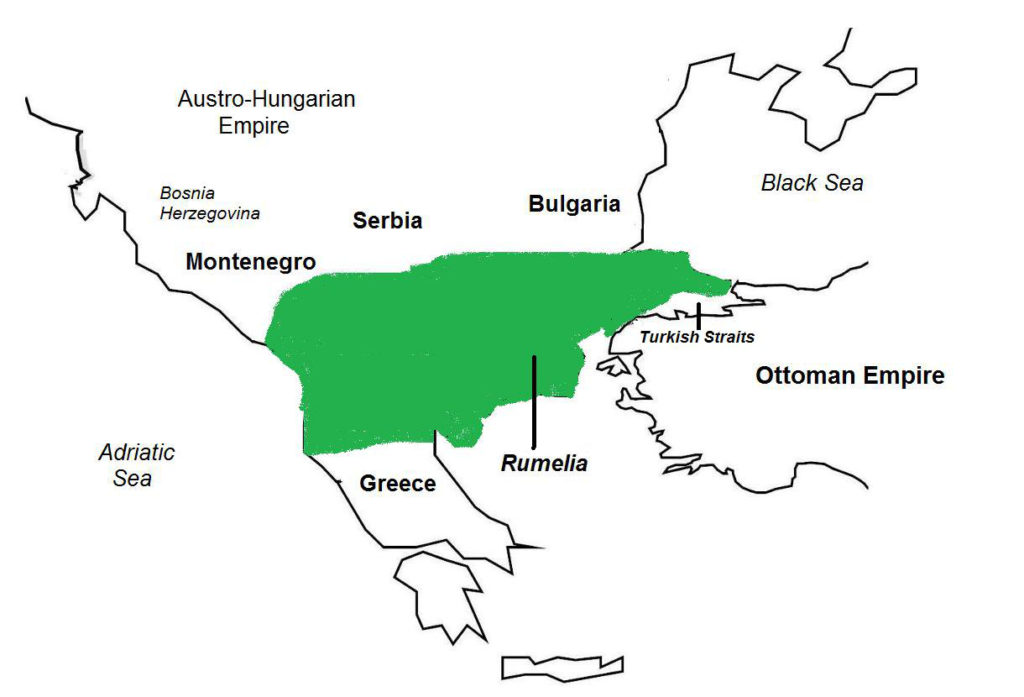

In Europe, the Ottomans had lost large areas of the Balkans, and all of its possessions in central and central eastern Europe. By 1910, Serbia, Bulgaria, Montenegro, and Greece had gained their independence. As a result, the Ottoman Empire’s last remaining possession in the European mainland was Rumelia (Map 4), a long strip of the Balkans extending from Eastern Thrace, to Macedonia, and into Albania in the Adriatic Coast. And even Rumelia itself was coveted by the new Balkan states, as it contained large ethnic populations of Serbians, Belgians, and Greeks, each wanting to merge with their mother countries.

The Russian Empire, seeking to bring the Balkans into its sphere of influence, formed a military alliance with fellow Slavic Serbia, Bulgaria, and Montenegro. In March 1912, a Russian initiative led to a Serbian-Bulgarian alliance called the Balkan League. In May 1912, Greece joined the alliance when the Bulgarian and Greek governments signed a similar agreement. Later that year, Montenegro joined as well, signing separate treaties with Bulgaria and Serbia.

The Balkan League was envisioned as an all-Slavic alliance, but Bulgaria saw the need to bring in Greece, in particular the modern Greek Navy, which could exert control in the Aegean Sea and neutralize Ottoman power in the Mediterranean Sea, once fighting began. The Balkan League believed that it could achieve an easy victory over the Ottoman Empire, for the following reasons. First, the Ottomans currently were locked in a war with the Italian Empire in Tripolitania (part of present-day Libya), and were losing; and second, because of this war, the Ottoman political leadership was internally divided and had suffered a number of coups.

Most of the major European powers, and especially Austria-Hungary, objected to the Balkan League and regarded it as an initiative of the Russian Empire to allow the Russian Navy to have access to the Mediterranean Sea through the Adriatic Coast. Landlocked Serbia also had ambitions on Bosnia and Herzegovina in order to gain a maritime outlet through the Adriatic Coast, but was frustrated when Austria-Hungary, which had occupied Ottoman-owned Bosnia and Herzegovina since 1878, formally annexed the region in 1908.

The Ottomans soon discovered the invasion plan and prepared for war as well. By August 1912, increasing tensions in Rumelia indicated an imminent outbreak of hostilities.