By late October 1975, Spanish officials had begun to hold clandestine meetings in Madrid with representatives from Morocco and Mauritania with regards to the region called Spanish Sahara, soon to be known as Western Sahara. As a precaution for war, in early November 1975, Spain carried out a forced evacuation of Spanish nationals from the territory. On November 12, further negotiations were held in the Spanish capital, culminating two days later (November 14) in the signing of the Madrid Accords, where Spain ceded the administration (but not sovereignty) of the territory, with Morocco acquiring the regions of El-Aaiún, Boujdour, and Smara, or the northern two-thirds of the region; while Mauritania the Dakhla (formerly Villa Cisneros) region, or the southern third; in exchange for Spain acquiring 35% of profits from the territory’s phosphate mining industry as well as off-shore fishing rights. Joint administration by the three parties through an interim government (led by the territory’s Spanish Governor-General) was undertaken in the transitional period for full transfer to the new Moroccan and Mauritanian authorities. (The Madrid Accords was not, and also since has not, been recognized by the UN, which officially continued to regard Spain as the “de jure”, if not “de facto”, administrative authority over the territory; furthermore, the UN deems the conflict region as occupied territory by Morocco and, until 1979, also by Mauritania.)

On February 26, 1976, Spain fully withdrew from the territory, which henceforth became universally called Western Sahara (although the UN already had referred to it as such by 1975). As per the agreement, Moroccan forces occupied their designated region (which Morocco soon called its Southern Provinces; also in 1979, Morocco would include the southern zone after Mauritania withdrew); and Mauritanian troops occupied Titchla, La Guera, and later Dakhla (as the capital), of its newly designated Saharan province of Tiris al-Gharbiyya. Then on April 14, 1976, the two countries signed an agreement that formally divided the territory into their respective zones of occupation and control.

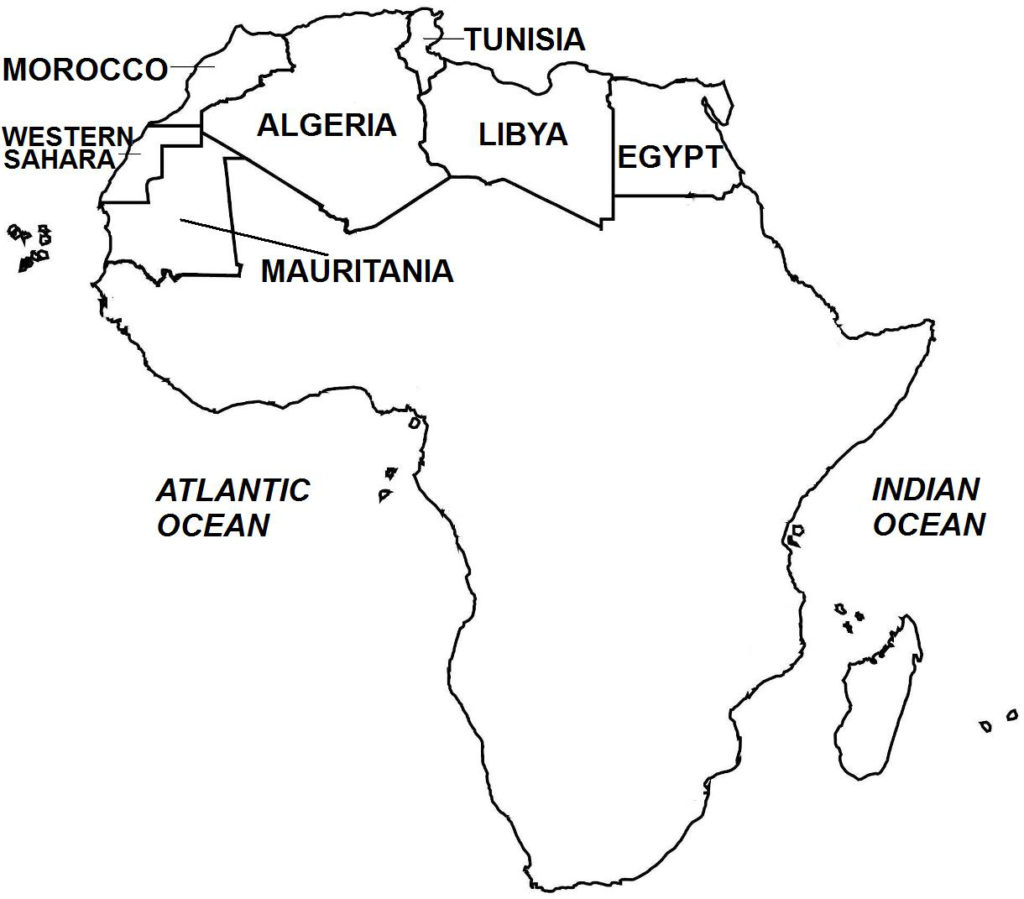

In the three-month period (November 1975–February 1976) during Spain’s withdrawal and replacement with Moroccan and Mauritanian administrations, tens of thousands of Sahrawis fled to the Saharan desert, and subsequently into Tindouf, Algeria. On February 27, 1976, one day after Spain withdrew from the territory, the Polisario Front declared the founding of the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR), with a government-in-exile based in Algeria.

(Taken from Western Sahara War – Wars of the 20th Centry – Volume 4)

Background For the Spanish government, Spanish Sahara had been a financial liability, the mostly barren, uninhabitable desert apparently yielding no economic benefits, with its rich maritime fishing resources bringing some export revenues but nonetheless incapable of reversing the need for Spain to allocate some amount of money annually to run the colony’s administration. But in the late 1940s, commercial quantities of high-grade phosphate deposits were discovered in Bou Craa, and the prospect of finding petroleum oil sparked Spain’s interest to hold onto the territory despite the growing wave of anti-colonialism that had been sweeping across Africa since the end of World War II.

In December 1960, the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) passed Resolution 1514 titled “Declaration on the Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples”, a landmark act that established the UN’s principle of decolonization; an implementing agency called the Special Committee on Decolonization, was formed to undertake the decolonization process. Based on Resolution 1514, the UNGA created a list called the “In-Trust and Non-self-governing Territories”, which contained territories that were still under colonial rule. In 1963, Spanish Sahara was placed on that list.

In April 1956, Morocco gained full independence after France and Spain ended their protectorates over the Moroccan state. The Istiqlal Party, an ultra-nationalist political party, advocated “Greater Morocco”, which called for the integration with present-day Morocco of lands and peoples historically governed by or subservient to the ancient Moroccan Sultanate. The concept of a Greater Morocco received broad support among the Moroccan population. The Moroccan government, led by King Mohammed V, officially did not endorse this policy, but also did not discourage – and even tacitly supported – its adherents from carrying out activities in support thereof.

Thus, the government remained neutral when, in the Ifni War (previous article) of October 1957, Moroccan militias of the Moroccan Army of Liberation (MAL) invaded Spanish possessions in Western Africa that Moroccan nationalists believed were historically part of Morocco. In the aftermath, Spain ceded a portion of its West African possessions. Then in 1963, Morocco fought a border war with Algeria in a failed attempt to capture territory in western Algeria that was historically part of Morocco and was included in the “Greater Morocco” concept.

By the first half of the 1970s, strong international pressure was bearing down on Spain to decolonize Spanish Sahara; the Spanish government’s justification of the territory being a Spanish “overseas province” was rejected by the UN. King Mohammed V led the call for decolonization, declaring that Spanish Sahara was historically a part of Morocco and thus must be returned to its owner. Mauritania also made a rival claim to the region, citing ethnic and cultural ties between northern Mauritanian peoples and Spanish Sahara’s Sahrawi tribes. Compounding Spain’s problems was the fact that since May 1973, Spanish Sahara itself was caught up in an uprising led by the Popular Front for the Liberation of Saguia el-Hamra and Río de Oro (or Polisario Front; Spanish: Frente Popular de Liberación de Saguía el Hamra y Río de Oro), a local Sahrawi armed militia that was fighting a guerilla war to end Spanish rule and achieve independence for Spanish Sahara.

In 1974, Spain finally acquiesced, announcing that it was ready to grant self-determination for the Sahrawi people corresponding to the UN resolutions. In December 1974, Spain carried out a population census in Spanish Sahara in order to prepare a voters list that would be used in a forthcoming referendum to determine the political wishes of the Sahrawi population. In a final bid to keep its economic, if not political, hold on the region, in November 1974, the Spanish government formed the Sahrawi National Union Party (PUNS; Spanish: Partido de Unión Nacional Saharaui), a political party mostly composed of the leaders and elders of the various Sahrawi tribes. Spain hoped to establish a PUNS-led government in either an autonomous or independent Sahara that would retain a pro-Spanish foreign policy.

On December 3, 1974, the UNGA passed Resolution 3292 declaring the UN’s interest in evaluating the political aspirations of Sahrawis in the Spanish territory. For this purpose, the UN formed the UN Decolonization Committee, which in May – June 1975, carried out a fact-finding mission in Spanish Sahara as well as in Morocco, Mauritania, and Algeria. In its final report to the UN on October 15, 1978, the Committee found broad support for annexation among the general population in Morocco and Mauritania. In Spanish Sahara, however, the Sahrawi people overwhelmingly supported independence under the leadership of the Polisario Front, while Spain-backed PUNS did not enjoy such support. In Algeria, the UN Committee found strong support for the Sahrawis’ right of self-determination.

Algeria previously had shown little interest in the Polisario Front and, in an Arab League summit held in October 1974, even backed the territorial ambitions of Morocco and Mauritania. But by summer of 1975, Algeria was openly defending the Polisario Front’s struggle for independence, a support that later would include military and economic aid and would have a crucial effect in the coming war.

Meanwhile, King Hassan II, the Moroccan monarch (son of King Mohammed V, who had passed away in 1961) actively sought to pursue its claim and asked Spain to postpone holding the referendum; in January 1975, the Spanish government granted the Moroccan request. In June 1975, the Moroccan government pressed the UN to raise the Saharan issue to the International Court of Justice (ICJ), the UN’s primary judicial agency. On October 16, 1975, one day after the UN Decolonization Committee report was released, the ICJ issued its decision, which consisted of the following four important points (the court refers to Spanish Sahara as Western Sahara):

1. At the time of Spanish colonization, “there were legal ties between this territory and the Kingdom of Morocco”;

2. At the time of Spanish colonization, “there were legal ties between this territory and the Mauritanian entity”;

3. There existed “at the time of Spanish colonization … legal ties of allegiance between the Sultan of Morocco and some of the tribes living in the territory of Western Sahara. They equally show the existence of rights, including some rights relating to the land, which constituted legal ties between the Mauritanian entity… and the territory of Western Sahara”;

4. The ICJ concluded that the evidences presented “do not establish any tie of territorial sovereignty between the territory of Western Sahara and the Kingdom of Morocco or the Mauritanian entity. Thus, the Court has not found legal ties of such a nature as might affect… the decolonization of Western Sahara and, in particular, … the principle of self-determination through the free and genuine expression of the will of the peoples of the Territory”.

Far from clarifying the issue, the ICJ’s involvement radicalized the parties involved, as each side focused on that part of the court’s decision that vindicated its claims. Morocco and Mauritania cited “legal ties” as supporting their respective claims, while the Polisario Front and Algeria pointed to “do not establish any tie of territorial sovereignty” and “the principle of self-determination through the free and genuine expression of the will of the peoples of the Territory” to put forward the Sahrawi peoples’ right of self- government. Spain’s chances of influencing the post-colonial Saharan territory began to wane. On September 9, 1975, Spanish foreign minister Pedro Cortina y Mauri and Polisario Front leader El-Ouali Mustapha Sayed met in Algiers, Algeria to negotiate the transfer of Saharan authority to the Polisario Front in exchange for economic concessions to Spain, particularly in the phosphate and fishing resources in the region. Further meetings were held in Mahbes, Spanish Sahara on October 22. Ultimately, these negotiations did not prosper, as they became sidelined by the accelerating conflict and greater pressures exerted by the other competing parties.