On November 3, 1969, U.S. President Richard Nixon addressed the nation on television and radio in what became known as the “silent majority” speech. In his address, Nixon stated “…to you, the great silent majority of my fellow Americans—I ask for your support”, in reference to the ongoing Vietnam War. Nixon was continuing his predecessor President Lyndon B. Johnson’s program of “Vietnamization”, that is, gradual American disengagement from the war, with the South Vietnamese military gradually taking over the fighting after a period of being built up. During his campaign for president, Nixon had stated that he had a “secret plan” to end the war, which anti-war advocates believed was a quick end of American involvement in Vietnam. But once in office, Nixon continued with the United States being involved in the war, stating that a sudden withdrawal “would result in a collapse of confidence in American leadership”, and that “a nation cannot remain great if it betrays its allies and lets down its friends”.

In October 1969, protesters staged a giant rally in Washington, D.C., prompting President Nixon to address the nation on November 3 with his “silent majority” speech. In it, he stated that the United States must continue with gradual disengagement from the war to achieve “peace with honor”. He concluded by appealing to the “great silent majority” for support. A White House official later stated that “silent majority” refers to “a large and normally undemonstrative cross-section of the country that…refrained from articulating its opinions on the war”. Nixon also said that he would not be “dictated by a minority staging demonstrations in the streets”.

(Taken from Vietnam War – Wars of the 20th Century – Twenty Wars in Asia)

Nixon and the Vietnam War In 1969, newly elected U.S. president, Richard Nixon, who took office in January of that year, continued with the previous government’s policy of American disengagement and phased troop withdrawal from Vietnam, while simultaneously expanding Vietnamization, with U.S. military advice and material support. He also was determined to achieve his election campaign promise of securing a peace settlement with North Vietnam under the Paris peace talks, ironically through the use of force, if North Vietnam refused to negotiate.

In February 1969, the Viet Cong again launched a large-scale Tet-like coordinated offensive across South Vietnam, attacking villages, towns, and cities, and American bases. Two weeks later, the Viet Cong launched another offensive. Because of these attacks, in March 1968, on President Nixon’s orders, U.S. planes, including B-52 bombers, attacked Viet Cong/North Vietnamese bases in eastern Cambodia (along the Ho Chi Minh Trail). This bombing campaign, codenamed Operation Menu, lasted 14 months (until May 1970), and segued into Operation Freedom Deal (May 1970-August 1973), with the latter targeting a wider insurgent-held territory in eastern Cambodia.

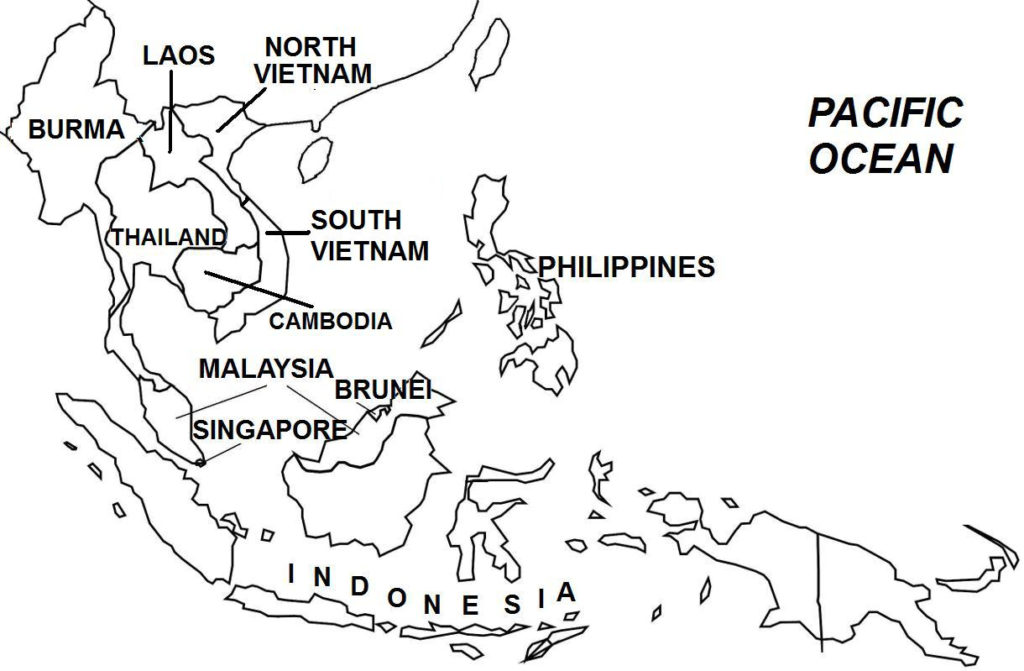

In the 1954 Geneva Accords, Cambodia had declared its neutrality in regional conflicts, a policy it maintained in the early years of the Vietnam War. However, by the early 1960s, Cambodia’s reigning monarch, Norodom Sihanouk, came under great pressure by the escalating war in Vietnam, and especially after 1963, when North Vietnamese forces occupied sections of eastern Cambodia as part of the Ho Chi Minh Trail system to South Vietnam. Then in the mid-1960s, Sihanouk signed security agreements with China and North Vietnam, where in exchange for receiving economic incentives, he acquiesced to the North Vietnamese occupation of eastern Cambodia. He also allowed the use of the port of Sihanoukville (located in southern Cambodia) for shipments from communist countries for the Viet Cong/NLF through a newly opened land route across Cambodia. This new route, called the Sihanouk Trail (Figure 5) by the Western media, became a major alternative logistical system by North Vietnam during the period of intense American air operations over the Laotian side of the Ho Chi Minh Trail.

In July 1968, under strong local and regional pressures, Sihanouk re-opened diplomatic relations with the United States, and his government swung to being pro-West. However, in March 1970, he was overthrown in a coup, and a hard-line pro-U.S. government under President Lon Nol abolished the monarchy and restructured the country as the Khmer Republic. For Cambodia, the spill-over of the Vietnam War into its territory would have disastrous consequences, as the fledging communist Khmer Rouge insurgents would soon obtain large North Vietnamese support that would plunge Cambodia into a full-scale civil war. For the United States (and South Vietnam), the pro-U.S. Lon Nol government served as a green light for American (and South Vietnamese) forces to conduct military operations in Cambodia.

The U.S. bombing operations on Viet Cong/North Vietnamese bases in eastern Cambodia forced North Vietnam to increase its military presence in other parts of Cambodia. The North Vietnamese Army seized control particularly of northeastern Cambodia, where its forces defeated and expelled the Cambodian Army. Then in response to the Cambodian government’s request for military assistance, starting in late April to early May 1970, American and South Vietnamese forces launched a major ground offensive into eastern Cambodia. The main U.S. objective was to clear the region of the North Vietnamese/Viet Cong in order to allow the planned American disengagement from the Vietnam War to proceed smoothly and on schedule. The offensive also served as a gauge of the progress of Vietnamization, particularly the performance of the South Vietnamese Army in large-scale operations.

In the nearly three-month successful operation (known as the Cambodian Campaign) which lasted until July 1970, American and South Vietnamese forces, which at their peak numbered over 100,000 troops, uncovered several abandoned major Viet Cong/North Vietnamese bases and dozens of underground storage bunkers containing huge quantities of materiel and supplies. In all, American and South Vietnamese troops captured over 20,000 weapons, 6,000 tons of rice, 1,800 tons of ammunition, 29 tons of communications equipment, over 400 vehicles, and 55 tons of medical supplies. Some 10,000 Viet Cong/North Vietnamese were killed in the fighting, although the majority of their forces (some 40,000) fled deeper into Cambodia. However, the campaign failed to achieve one of its objectives: capturing the Viet Cong/NLF leadership COSVN (Central Office for South Vietnam). The Nixon administration also came under domestic political pressure: in December 1970, and U.S. Congress passed a law that prohibited U.S. ground forces from engaging in combat inside Cambodia and Laos.

Before the Cambodian Campaign began, President Nixon had announced in a nationwide broadcast that he had committed U.S. ground troops to the operation. Within days, large demonstrations of up to 100,000 to 150,000 protesters broke out in the United States, with the unrest again centered in universities and colleges. On May 4, 1970, at Kent State University, Ohio, National Guardsmen opened fire on a crowd of protesters, killing four people and wounding eight others. This incident sparked even wider, increasingly militant and violent protests across the country. Anti-war sentiment already was intense in the United States following news reports in November 1969 of what became known as the My Lai Massacre, where U.S. troops on a search and destroy mission descended on My Lai and My Khe villages and killed between 347 and 504 civilians, including women and children.

American public outrage further was fueled when in June 1971, the New York Times began publishing the “Pentagon Papers” (officially titled: United States – Vietnam Relations, 1945–1967: A Study Prepared by the Department of Defense), a highly classified study by the U.S. Department of Defense that was leaked to the press. The Pentagon Papers showed that successive past administrations, including those of Presidents Truman, Eisenhower, and Kennedy, but especially of President Johnson, had many times misled the American people regarding U.S. involvement in Vietnam. President Nixon sought legal grounds to stop the document’s publication for national security reasons, but the U.S. Supreme Court subsequently decided in favor of the New York Times and publication continued, and which was also later taken up by the Washington Post and other newspapers.

As in Cambodia, the U.S. high command had long desired to launch an offensive into Laos to cut off the logistical portion of the Ho Chi Minh Trail system located there. But restrained by Laos’ official neutrality, the U.S. military instead carried out secret bombing campaigns in eastern Laos and intelligence gathering operations (the latter conducted by the top-secret Military Assistance Command, Vietnam – Studies and Observations Group, MACV-SOG that involved units from Special Forces, Navy SEALS, U.S. Marines, U.S. Air Force, and CIA) there.

The success of the Cambodian Campaign encouraged President Nixon to authorize a similar ground operation into Laos. But as U.S. Congress had prohibited American ground troops from entering Laos, South Vietnamese forces would launch the offensive into Laos with the objective of destroying the Ho Chi Minh Trail, with U.S. forces only playing a supporting role (and remaining within the confines of South Vietnam). The operation also would gauge the combat capability of the South Vietnamese Army in the ongoing Vietnamization program.