On November 30, 1939, the Winter War began between the Soviet Union and Finland with Soviet planes bombing Helsinki, Viipuri, and other locations, killing civilians and destroying infrastructures. The next day, at the Gulf of Finland, the Soviet cruiser Kirov and her escort of two destroyers attempted to bombard Hanko but instead were fired upon by Finnish coastal batteries at Russaro Island, taking hits and forced to return to their base at Kronstadt, near Leningrad. Shortly after the Red Army launched its invasion, Finland appealed to the League of Nations, which on December 14, 1939, expelled the Soviet Union and called on member states to help Finland.

On December 1, 1939, anticipating a quick campaign, the Soviet Union formed a new Finnish state, the Finnish Democratic Republic, at Terijoki, led by exiled Finnish communist leaders, in the hope that the new regime would encourage the Finnish working class and general population to rise up in revolt and overthrow the Helsinki government. As it turned out, no uprising occurred; instead, Finns of all social classes rallied behind their government in Helsinki.

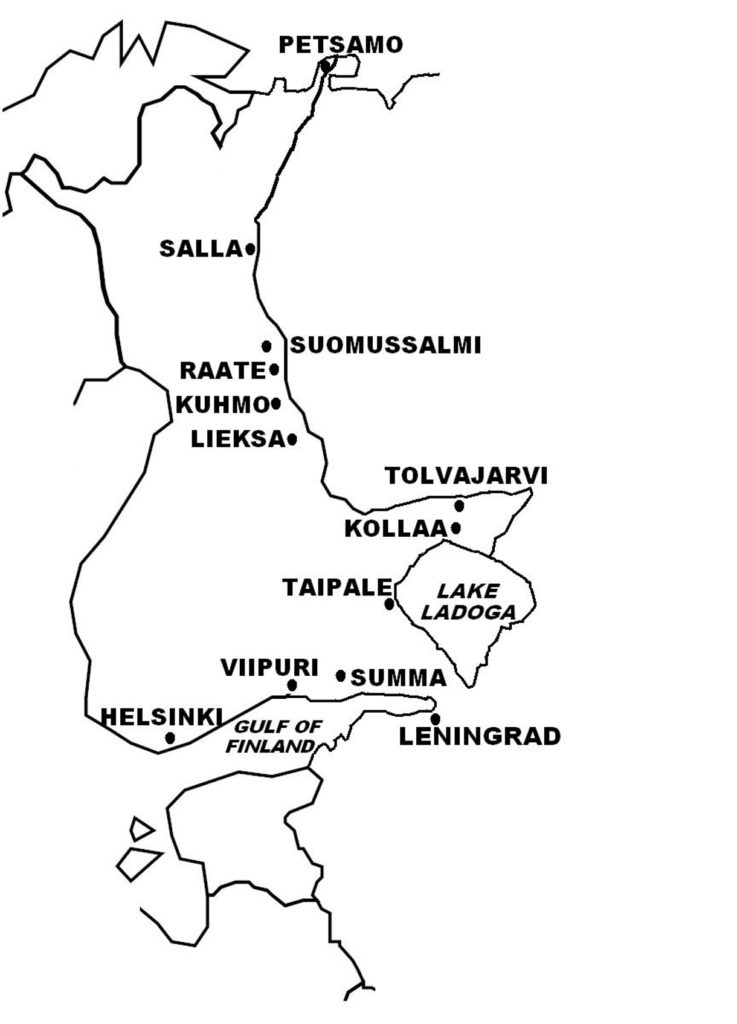

At the same time, the Red Army launched its ground campaign along the whole length of the Soviet-Finnish border, with the major concentration located at the Karelian Isthmus and north of Lake Ladoga, as well as secondary attacks further north, at Lieksa, Kuhmo, Suomussalmi, Salla, and Petsamo. In the far north, the Soviet Navy bombarded Petsamo, followed the next day by Red Army troops taking control of the city, which was earlier evacuated by the small Finnish garrison.

(Taken from Winter War – Wars of the 20th Century – World War II in Europe)

The Soviet Union was eager for war, and Stalin and most of the Soviet High Command were fully confident of achieving success in a short campaign, perhaps as little as a few days, and in blitzkrieg fashion with overwhelming force, essentially rivaling what the Germans had achieved in their conquest of the western half of Poland. Soviet optimism was borne from its highly successful campaign in the eastern half of Poland just two months earlier, where the Polish Army put up only token resistance. Stalin anticipated a similar lackluster performance by the Finns.

On November 26, 1939, Mainilla, a Russian frontier village in the Karelian Isthmus, was attacked by artillery fire. The Soviets put the blame for the attack on the Finnish forces positioned just across the border, and then demanded that Finland issue an apology and move back its forces 12-16 miles from the border. When the Finnish government denied any involvement and refused to move back its forces, the Soviet Union repealed the Soviet-Finnish non-aggression pact, and on November 29, 1939, cut diplomatic relations with Finland.

By then, Stalin was impatient and ready to go to war, as large numbers of Soviet forces had already been brought forward in September-October 1939 and were massed along the 600-mile Soviet-Finnish border. With the deployment of first-line assault forces in November 1939, the Red Army was poised to attack. The Soviet invasion force totaled 540,000 troops, 3,000 tanks, and 3,000 planes, an overwhelming superiority in numbers over the Finnish Army by the ratio of 3:1 in manpower, 100:1 in tanks, and 30:1 in planes.

Guiding Soviet offensive strategy was the Deep Battle concept developed in the 1930s, which envisioned the coordinated use of massive land, sea, and air power to advance deep and quickly inside enemy territory to achieve complete tactical and strategic victory. But in 1937-1938, Stalin launched a major purge of the Red Army officer corps (some 50% were affected), which was part of the larger Great Purge involving the Soviet communist party itself and other perceived enemies of the state. As a result, by 1939, very few in the Soviet High Command and newly appointed officers who had been promoted more for party loyalty than military competence, knew how to implement Deep Battle in actual warfare. Furthermore, all Red Army units had a political commissar, who ensured compliance by officers and men of the communist party line and had the authority to countermand orders by unit commanders, if they ran contrary to party policies. A few Soviet generals resisted the optimism of the Soviet High Command regarding the Finnish campaign, and advised caution and more preparation for the invasion. General Kirill Meretskov, over-all commander of the invasion force, also (correctly) warned that the Finnish terrain, which was characterized by many lakes, rivers, swamps, and forest, could be a major problem for the Red Army.

Soviet forces positioned along the whole length of the Finnish-Soviet border, from the Gulf of Finland in the south to Murmansk in the north, were deployed as follows: Soviet 7th Army, with nine divisions, was tasked with taking the Karelian Isthmus including Viipuri (Finland’s second major city); Soviet 8th Army, with six divisions, would advance through the north of Lake Ladoga, and executing a flanking maneuver, attack the rear of the Finnish Mannerheim Line; Soviet 9th Army, with three divisions, would attack west through the central region and cut Finland in half; and Soviet 14th Army, with three divisions, would advance from Murmansk and take Petsamo. All Soviet armies were supported by large numbers of armored, artillery, and air units.

The Finnish Army, which was greatly outnumbered in manpower and weapons, was led by Marshall Carl Gustaf Mannerheim, who organized a defensive strategy based on the assumption that the fighting would focus in and around the Karelian Isthmus. The Army of the Isthmus of six divisions (II and III Army Corps; some 150,000 troops), comprising the bulk of the 180,000-strong Finnish Army, was tasked to defend the Karelian Isthmus, while two divisions (IV Army Corps, 20,000 troops) would secure the left flank, north of Lake Ladoga. Mannerheim had (incorrectly) thought that the rest of the border right up to Petsamo, with its difficult terrain and harsh climate, was an unlikely invasion area, and thus was only lightly manned by Finnish border guards, civil guards, and reserve units organized as the North Finland Group. Unknown to the Finns, some 120,000 Soviet troops, supported by air, artillery, and air units, were poised to attack there as well.

The focal point of the Finnish defense in the Karelian Isthmus was the Mannerheim Line, some 80 miles extending from the shore of the Gulf of Finland and Summa in the west to Taipale at the edge of Lake Ladoga in the east, and fortified with 157 machinegun and artillery bunkers throughout its length, with the heaviest concentration of 41 bunkers located at Summa. The Line was not evenly fortified along its length, at some points only strengthened with barbed wire, boulders, and concrete slabs, or felled trees, and incorporated natural obstacles aimed to slow down the advance of enemy armor and infantry. The Line’s flanks were defended by coastal batteries at the shores of the Gulf of Finland and Lake Ladoga. Mannerheim did not think highly of the Line, believing that it would be breached in 7-10 days. In Karelia north of Lake Ladoga all the way to Petsamo in the north, the Finns possessed only less fortified defenses at Tolvajarvi, Kollaa, and Uomma-Impilahti, and individual Finnish commanders were encouraged to use guerilla tactics emphasizing speed, surprise, and deception and to incorporate the elements of terrain, long, dark winter nights, and weather conditions to meet the threat of the much larger Russian forces.