On October 27, 1962, all-out war between the United States and the Soviet Union was averted when Soviet flotilla commander Vasily Arkhipov refused to allow the Russian submarine B-59 to fire its nuclear torpedoes at a U.S. Navy flotilla. The American flotilla, consisting of nine destroyers and the aircraft carrier USS Randolph had detected the B-59 and dropped depth charges to force the Soviet submarine to surface to be identified. The refusal by Arkhipov to retaliate by firing the B-59‘s nuclear torpedoes, as suggested by the other two senior officers aboard (agreement of all three was required), prevented the incident from escalating into an all-out nuclear war, as the United States would have reacted militarily to the B-59’s action. Instead, the Soviet submarine surfaced.

(Taken from Cuban Missile Crisis – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 2)

Background In the nuclear arms race between the two superpowers, the United States held a decisive edge over the Soviet Union, both in terms of the number of nuclear missiles (27,000 to 3,600) and in the reliability of the systems required to deliver these weapons. The American advantage was even more pronounced in long-range missiles, called ICBMs (Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles), where the Soviets possessed perhaps no more than a dozen missiles with a poor delivery system in contrast to the United States that had about 170, which when launched from the U.S. mainland could accurately hit specific targets in the Soviet Union.

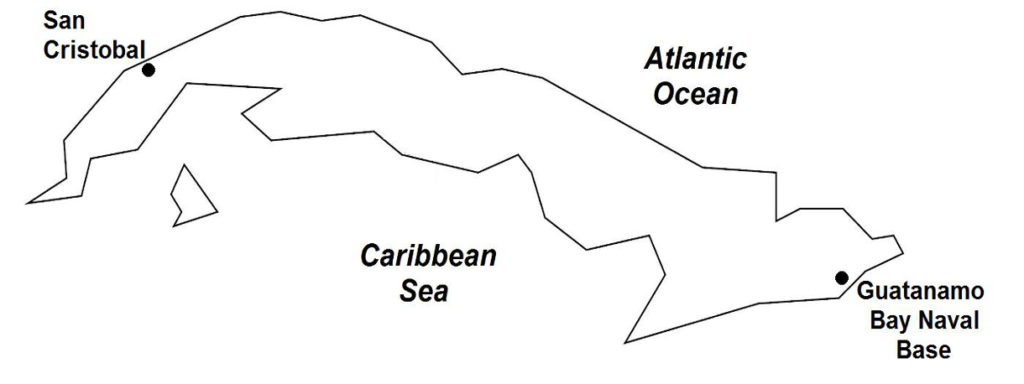

The Soviet nuclear weapons technology had been focused on the more likely war in Europe and therefore consisted of shorter range missiles, the MRBMs (medium-range ballistic missiles) and IRBMs (intermediate-range ballistic missiles), both of which if installed in Cuba, which was located only 100 miles from southeastern United States, could target portions of the contiguous 48 U.S. States. In one stroke, such a deployment would serve Castro as a powerful deterrent against an American invasion; for the Soviets, they would have invoked their prerogative to install nuclear weapons in a friendly country, just as the Americans had done in Europe. More important, the presence of Soviet nuclear weapons in the Western Hemisphere would radically alter the global nuclear weapons paradigm by posing as a direct threat to the United States.

In April 1962, Premier Khrushchev conceived of such a plan, and felt that the United States would respond to it with no more than a diplomatic protest, and certainly would not take military action. Furthermore, Premier Khrushchev believed that President Kennedy was weak and indecisive, primarily because of the American president’s half-hearted decisions during the failed Bay of Pigs Invasion in April 1961, and President Kennedy’s weak response to the East German-Soviet building of the Berlin Wall in August 1961.

A Soviet delegation sent to Cuba met with Fidel Castro, who gave his consent to Khrushchev’s proposal. Subsequently in July 1962, Cuba and the Soviet Union signed an agreement pertinent to the nuclear arms deployment. The planning and implementation of the project was done in utmost secrecy, with only a few of the top Soviet and Cuban officials being informed. In Cuba, Soviet technical and military teams secretly identified the locations for the nuclear missile sites.

In August 1962, U.S. reconnaissance flights over Cuba detected the presence of powerful Soviet aircraft: 39 MiG-21 fighter aircraft and 22 nuclear weapons-capable Ilyushin Il-28 light bombers. More disturbing was the discovery of the S-75 Dvina surface-to-air missile batteries, which were known to be contingent to the deployment of nuclear missiles. By late August, the U.S. government and Congress had raised the possibility that the Soviets were introducing nuclear missiles in Cuba.

By mid-September, the nuclear missiles had reached Cuba by Soviet vessels that also carried regular cargoes of conventional weapons. About 40,000 Soviet soldiers posing as tourists also arrived to form part of Cuba’s defense for the missiles and against a U.S. invasion. By October 1962, the Soviet Armed Forces in Cuba possessed 1,300 artillery pieces, 700 regular anti-aircraft guns, 350 tanks, and 150 planes.

The process of transporting the missiles overland from Cuban ports to their designated launching sites required using very large trucks, which consequently were spotted by the local residents because the oversized transports, with their loads of canvas-draped long cylindrical objects, had great difficulty maneuvering through Cuban roads. Reports of these sightings soon reached the Cuban exiles in Miami, and through them, the U.S. government.