By early 1949, the Greek Armed Forces held an overwhelming manpower and material advantage over the communist rebels of the DSE (Democratic Army of Greece; Greek transliteration: Dimokratikos Stratos Elladas) in the Greek Civil War. As well, American weapons continued to arrive in Greece. By then, the rebels were hard pressed to gain new recruits, more so since their civilian base of support had been resettled into towns, while other communist sympathizers had been executed, jailed or had fled into exile abroad.

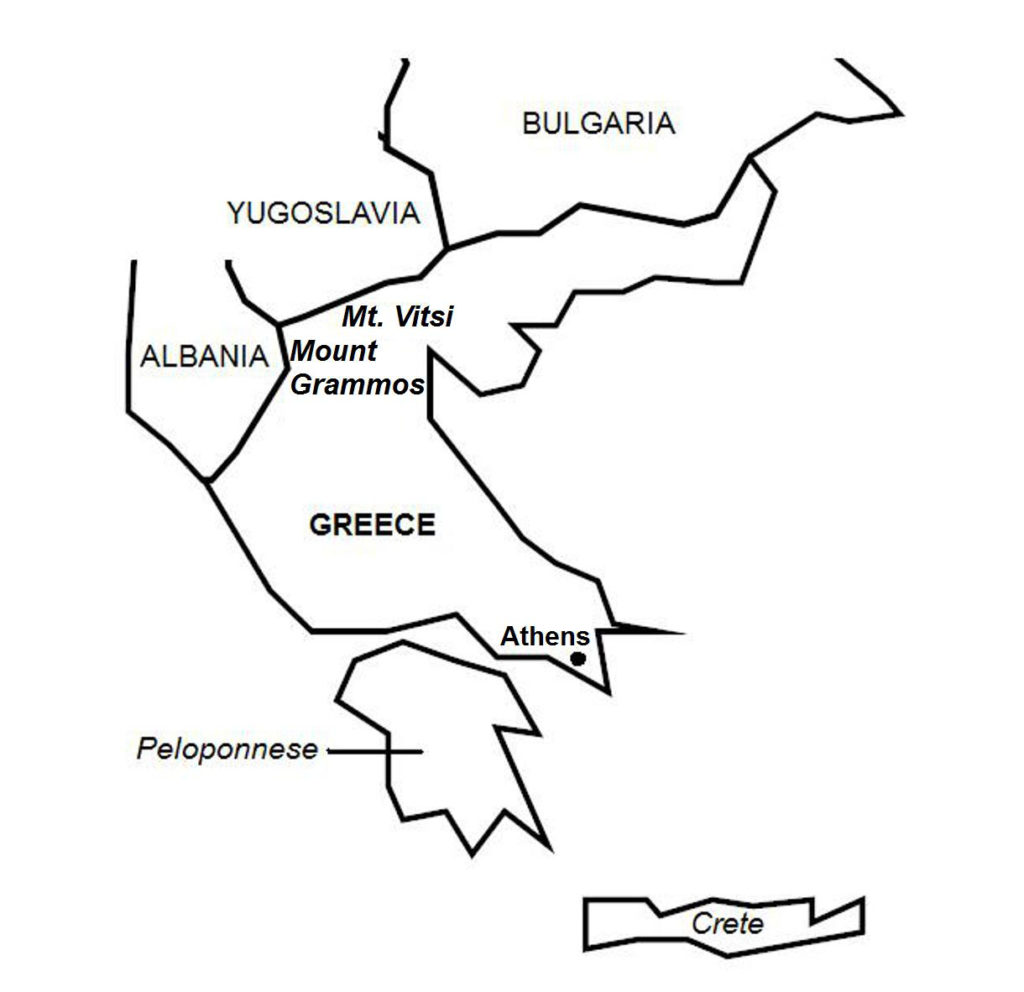

In January 1949, in what became the first of a series of battles that ended the war, the Greek Army inflicted a decisive defeat on the rebels in the Peloponnese region, and gained full control of southern Greece. Then in June, another powerful offensive involving 70,000 troops cleared central Greece of insurgents, who were forced to retreat north. In August 1949, the Greek Army launched its final offensive in northern Greece, capturing the last rebel strongholds on Mounts Grammos and Vitsi and forcing the DSE to retreat to Albania and Bulgaria. Small scattered rebel units in Greece soon also succeeded in escaping from Greece. Most of the KKE (Greek Communist Party; Greek transliteration: Kommounistikó Kómma Elládas) and DSE exiles eventually settled in Eastern Bloc countries and the Soviet Union. On October 16, 1949, the KKE announced a “temporary ceasefire” which, unknown at the time, led to a permanent end of the war.

Some 158,000 persons died in the war, while one million people were displaced from their homes. In the following years, Greece rebuilt its devastated economy, which was achieved partly by American financial assistance under the European Recovery Program (more commonly known as the Marshall Plan).

As a result of the civil war, Greece experienced a long period of political instability caused by fractious politics between the political left and right, which culminated in a military coup in April 1967 that established a right-wing military junta. Greece remained under the sphere of the Western democracies, joined NATO in 1952, and kept close military and economic ties with the United States. In July 1974, the junta collapsed and Greece began its transition to democracy by establishing an interim civilian government and holding free elections. Also in 1974, the monarchy was abolished in a national referendum and the country then established a parliamentary republic.

(Taken from Greek Civil War – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 3)

Background of the Greek Civil War The Greek Civil War has its origin in World War II, in April 1941 when the Axis Powers of Germany, Italy, and Bulgaria invaded and overrun Greece and defeated and expelled the Greek and British forces. Greece’s King George II and the Greek government fled to exile in Britain-controlled Egypt, where they set up a government-in-exile in Cairo. In Greece, the Axis partitioned the country into zones of occupation and set up a collaborationist government in Athens.

Organized resistance to the occupation began in July 1941 when officers and members of the Greek Communist Party, or KKE (Greek transliteration: Kommounistikó Kómma Elládas), many of whom had been jailed by Greece’s right-wing military government before the war but had escaped following the Axis invasion, secretly met and formed a unified “popular front” to fight the occupation forces and collaborationist government. This idea bore fruit when in September 1941, the KKE and three other leftist organizations formed the National Liberation Front, or EAM (Greek transliteration: Ethniko Apeleftherotiko Metopo), whose aims were to liberate Greece, and to advance “the Greek people’s sovereign right to determine its form of government”.

In February 1942, EAM formed an armed wing, the Greek People’s Liberation Army, or ELAS (Greek transliteration: Ellinikós Laïkós Apeleftherotikós Stratós), which carried out guerilla and sabotage operations against the Axis forces and collaborationist government. Success in the battlefield allowed EAM-ELAS to gain control of the Greek countryside and mountain areas, drawing active support from the rural population (communist and non-communists), and allowing the resistance to grow to 50,000 fighters and 500,000 non-combat auxiliaries. Perhaps as much as three-quarters of Greek territory came under EAM-ELAS control, although the major urban areas, including Athens, continued to be held by the Axis.

Other resistance movements (all advocating non-communist ideologies) also operated during the occupation, with the two major of these being the National Republican Greek League, or EDES (Greek transliteration: Ethnikos Dimokratikos Ellinikos Syndesmos, abbreviated) and the National and Social Liberation, or EKKA (Greek transliteration: Ethniki kai Koinoniki Apeleftherosis). These groups had much smaller militias and were less military capable of confronting the enemy than was EAM-ELAS. Britain provided technical and material support to all Greek resistance groups, including EAM-ELAS, whose communist ideology were at odds with the British.

The Greek resistance groups were hostile to each other, and skirmishes broke out among them as did they against the Axis forces/collaborationist militias. The British and EAM-ELAS also were wary of each other with regards to post-war Greece and the country’s political future. This mutual distrust initially was set aside because of the need to fight a common enemy, but gradually increased toward war’s end when the Axis defeat became certain.

The British were concerned that EAM-ELAS, with its overtly pro-Soviet inclination, would prevail in the war and transform post-war Greece into a Marxist state aligned with the Soviet Union. For the British, a communist country in the Mediterranean Sea, especially one that potentially would allow a Soviet maritime presence through a naval agreement or the use of ports would threaten the Suez Canal, Britain’s vital link to India and other British colonies in Asia. Britain was determined that King George II should return to Greece, which would guarantee the formation of a conservative government friendly to British interests.

Because of its multi-party, multi-ideology origins, EAM-ELAS officially promoted a democratic policy. However, since it was dominated by the KKE (comprising the largest constituent organization), EAM-ELAS was formed and functioned along communist lines. EAM-ELAS also was firmly opposed to the return of Greece’s government-in-exile, because of fears of a return to the pre-war right-wing (i.e. repressive) regime, as well as to the return of the king, who had supported that regime.

In March 1944, EAM established a quasi-government called the Political Committee of National Liberation, or PEEA (Greek transliteration: Politiki Epitropi Ethikis Apeleftherosis), commonly known as the “Mountain Government”. The PEEA held legislative elections where women, for the first time in Greece, were allowed to vote. The rebel government called for continuing the resistance against the occupation, “destruction of fascism”, and the independence and sovereignty of Greece.

In April 1944, a mutiny broke out in Egypt among soldiers of the exiled Greek Armed Forces, who declared that the government-in-exile was irrelevant and needed to be replaced by a new, progressive government that genuinely represented the changes taking place in Greece. British authorities quelled the mutiny, and jailed the soldiers.

The mutiny, however, led to the end of the government-in-exile. In May 1944, under British sponsorship, representatives from the various Greek political parties and resistance groups met and held talks in Beirut, Lebanon. These talks, called the Lebanon Conference, led to the formation of a coalition government (called the government of national unity) led by Prime Minister Georgios Papandreou. Of the 24 posts in the new government, 6 were allocated to EAM. The conference also agreed that King George’s return to Greece would be postponed and subject to a referendum that would decide the fate of the monarchy.

By the fall of 1944, the Soviet Army had broken through in Eastern Europe. To avoid being cut off, in October of that year, the Germans (who, by this time, were the remaining occupation forces in Greece) retreated north. With the Germans out of Greece, the British soon arrived in Athens, followed by Prime Minister Papandreou’s government which began to take over the administrative duties left behind by the fallen collaborationist regime.

One month earlier, the various armed resistance groups had agreed to subordinate their militias under the command of the British Army. EAM-ELAS controlled much of Greece but wanted to preserve Allied unity and therefore did not pre-empt the British by occupying and taking over Athens, although it was capable of doing so.

Unbeknown to EAM-ELAS, however, the fate of post-war Greece already had been decided secretly by Britain and the Soviet Union. In a number of meetings with British officials, Soviet leader Joseph Stalin had indicated that the Soviet Union was not interested in Greece. In October 1944, in what became known as the Percentages Agreement, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and Stalin delineated their respective countries’ post-war spheres of influence in the Balkans and parts of Eastern Europe: Yugoslavia and Hungary would be split evenly between them; Romania and Bulgaria would have Soviet majority control; and Greece would fall under British majority control.