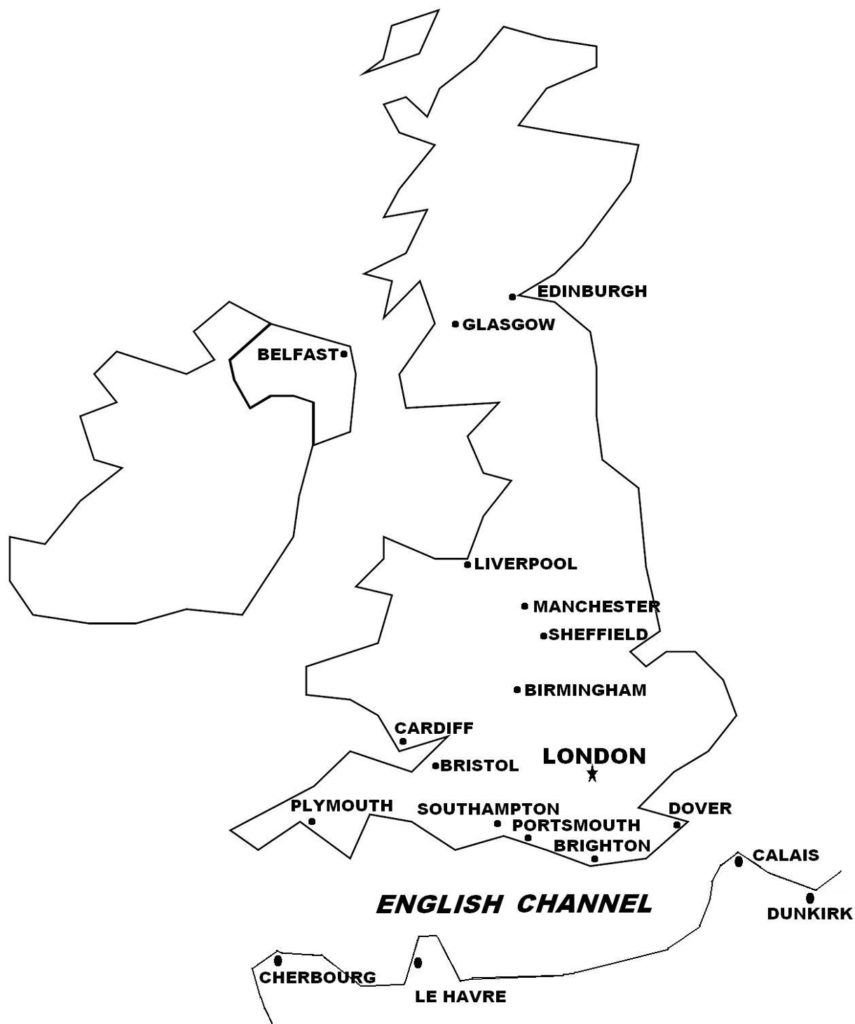

On September 7, 1940, in what the British called the “Blitz”, the German Luftwaffe began a series of concentrated attacks of British urban centers, launching 600 bombers and 400 fighters that came in successive bombing waves on the center of London. Large-scale Luftwaffe bombing attacks continued for the next several weeks, hitting residential, industrial, and military targets and public works facilities in many major centers across Britain, including Bristol, Cardiff, Portsmouth, Plymouth, Southampton, Swansea, Birmingham, Belfast, Coventry, Glasgow, Manchester, and Sheffield. Some 40,000 civilians were killed, and 50,000 wounded, while one million houses were destroyed or damaged.

On September 15, 1940, in what is known as the “Battle of Britain Day”, a combined 1,700 planes (1,100 Luftwaffe and 600 RAF) fought a day-long air battle in the skies over London, in what Goering hoped would be the ultimate destruction of the RAF. By then, the constant German pressure during Alderagriff (since August 24) had greatly strained RAF strength of No. 11 Group (which was tasked to defend southeast England, including London), but the sudden shift in Luftwaffe concentration toward the cities allowed the RAF a respite. Also at this time, a crisis within the RAF was reaching the breaking point, as Air Vice-Marshal Trafford Leigh-Mallory, commander of RAF No. 12 Group (for southwest England), criticized Air Chief Marshal Dowding’s conduct of the air campaign, particularly the use of small RAF units to meet the massive German fleets. Leigh-Mallory, like many senior RAF commanders, favored large formations (per the “Big Wing” strategy) to meet the Luftwaffe in pitched air battles. As a result, Downing was dismissed as commander of RAF Fighter Command.

Despite No. 11 Group’s losses, the RAF over-all was nowhere near collapse, for in fact, British aircraft production, as were the other war-related industries, was growing. Furthermore, the air battles, fought in British territory, gave the RAF considerable advantages: downed RAF pilots who had parachuted to safety were quickly sent up to fight again in another plane, while RAF planes were near their fuel, supply, and communication lines. The Luftwaffe fought against tremendous odds: downed pilots and air crews on land faced certain capture, or worse, lynching by angry mobs, and those on the sea, death by drowning or exposure to the elements; and Luftwaffe planes operated far from fuel and logistical lines, e.g. the Messerschmitt Bf 109 fighter plane, which functioned as a bomber escort, had only ten minutes of flying time left upon arriving in Britain, and after which it had to turn back for Germany, leaving the bombers undefended from RAF interceptors.

On September 17, 1940, with mounting Luftwaffe losses and the RAF clearly not verging on collapse, Hitler acknowledged before the German High Command that the German air effort in Britain would probably not succeed, and gave instructions that preparations for Operation Sea Lion be scaled back. Nevertheless, Hitler stated that the air attacks on Britain must continue, as ending the campaign would be an admission of defeat, and that they were to be used as a cover for the fact that the German military had begun preparing (since August 1940) for its most ambitious operation of all, the conquest of the Soviet Union.

By October 1940, the “weather window” for the invasion of Britain had closed, as German planning had taken into account that the onset of bad weather over the English Channel would greatly impede a cross-channel naval operation. On October 13, Hitler pushed back Operation Sea Lion to the spring of 1941. The air offensive continued, although by November 1940, the Luftwaffe shifted to nighttime attacks, as daylight operations were taking a heavy toll on men and aircraft. Official British historiography points to October 31, 1940 as the date that the Battle of Britain ended, although German air attacks would continue for many more months, sometimes with great intensity particularly in October-December 1940 and even well into early May 1941. But by spring of 1941, Hitler’s attention had invariably turned to other theaters of the war, first to the Balkans with the invasions of Yugoslavia and Greece both in April 1941, and then to his greatest ambition of all, the conquest of the Soviet Union (Operation Barbarossa), set for June 1941. In the process, the bulk of the Luftwaffe was moved to the east, greatly easing the pressure off Britain.

(Taken from Battle of Britain – Wars of the 20th Century – World War II in Europe)

Aftermath In the Battle of Britain, the Luftwaffe sustained some 2,600 airmen killed, wounded, or captured, and 1,700 planes destroyed or damaged (comprising 40% of the entire fleet). While German aircraft production continued, this considerable loss of men and aircraft meant fewer Luftwaffe resources for Operation Barbarossa. At the end of hostilities in May 1941, Hitler continued to believe that Britain was effectively knocked out of the European war and posed no serious threat on the continent. However, leaving Britain unconquered turned out to be one of Hitler’s great strategic mistakes. With German military resources soon directed at the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe, Britain recovered and grew militarily. Then with the United States entering the war on the British side in December 1941, and in alliance with the other Allied partners, the British as part of the Allied force would return to the continent in June 1944.

Contemporary thinking at the time attributed British success against the Luftwaffe to the RAF fighter pilots in their Hawker Hurricanes and Supermarine Spitfires, a depiction embodied in Churchill’s words, “Never in the field of human conflict was so much owed by so many to so few”. Only in the post-World War II period was it revealed the critical role played by the ultra-secret Dowding system, which was known only to very few top-level officials in government and the military. The counter-argument is that while RAF No. 11 Group had been mauled during Operation Alderangriff, suffering heavy losses in men and planes, and many destroyed airfields and supporting infrastructures, the other RAF Groups (10, 12, and 13) remained powerful, and production of aircraft continued.