On August 18, 1965, U.S. Marines launched Operation Starlite aimed at pre-empting a Viet Cong attack on Chu Lai Air Base. With information provided by South Vietnamese military intelligence, the operation destroyed an insurgent camp on the Van Tuong peninsula in nearly one week of heavy fighting (August 18-24, 1965). The U.S. force consisted of 5,500 personnel, while the Viet Cong totaled 1,500. Casualties were: U.S. 45 killed, 200 wounded; Viet Cong – 600 killed, 42 captured.

(Taken from Vietnam War – Wars of the 20th Century – Twenty Wars in Asia)

Fighting along Vietnam’s Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) In the northern part of South Vietnam (which the South Vietnamese government designated as I Corps Tactical Zone), U.S. Marines, who were based at Da Nang, Phu Bai, and Chu Lai, supplemented by South Vietnamese forces, were tasked with defending the areas south of the DMZ. The U.S. Marines launched several search and destroy missions in the surrounding village areas (which were under the nominal control of the Viet Cong/NLF). These operations yielded little results, as the Viet Cong refused to fight in the open, but retreated to the jungles, only to return after the Americans had departed. Unable to locate the enemy, the U.S. Marines changed their strategy, and instead implemented a “hearts and minds” campaign of providing social, medical, economic, and political programs, aimed at winning the support of the local population. Ultimately, the “hearts and minds” program proved only partially successful, as Viet Cong influence in these agriculturally rich lowland coastal areas remained strong. General Westmoreland also viewed these conciliatory efforts by the U.S. Marines as contrary to the American war strategy of seeking and destroying the Viet Cong.

By mid-1966, North Vietnamese infiltrations across the DMZ had increased considerably. North Vietnam had timed these infiltrations to take advantage of the ongoing massive civilian unrest occurring in South Vietnam. In response, the U.S. military launched offensives to counteract these infiltrations. In August 1966, under Operation Starlite, U.S. Marines pre-empted a North Vietnamese planned assault on the U.S. Marine base at Chu Lai. The North Vietnamese were forced to retreat to their side of the DMZ, where they regrouped and again crossed the DMZ into South Vietnam, which was met with U.S. Marines in Operation Prairie, which again forced the enemy to fall back across the DMZ.

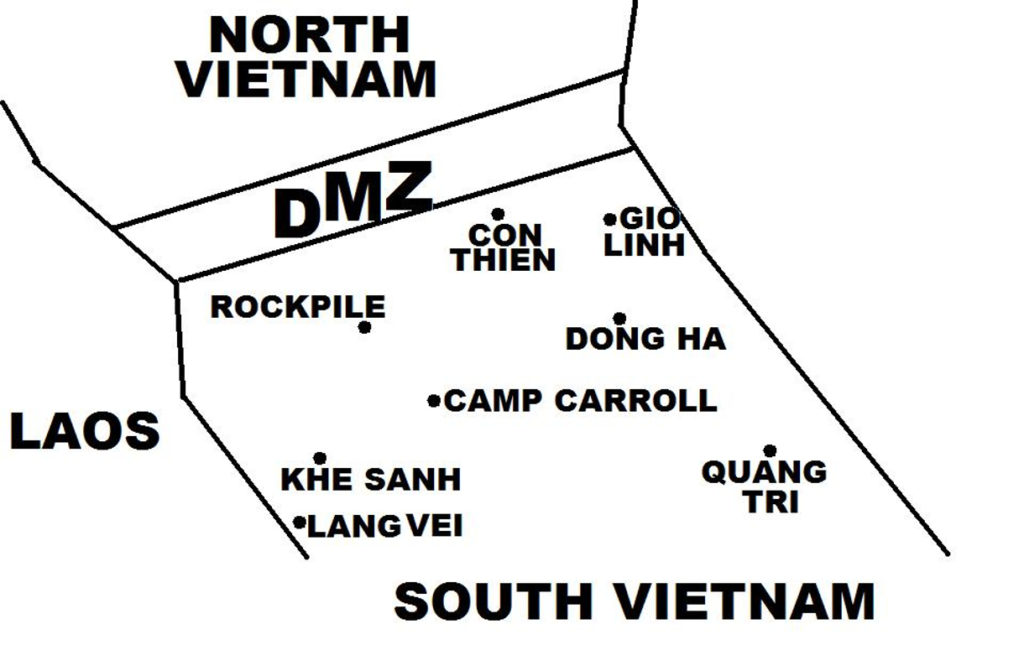

Because of the increased North Vietnamese pressure, by mid-1966, the U.S. Marines had established a series of combat bases across and adjacent to the DMZ; these bases included Khe Sanh, Dong Ha, Con Thien, and Gio Linh, all of which were supported by the artillery bases of Camp Carroll and Rockpile (Figure 6).

In June 1966, North Vietnamese forces again attacked across the DMZ, but were repulsed by U.S. Marines, supported by South Vietnamese units and American air, artillery, and naval forces. U.S. forces then launched Operation Hastings, leading to three weeks of large battles near Dong Ha and ending with the North Vietnamese withdrawing back across the DMZ. The year 1966 also saw the United States greatly escalating the war, with U.S. deployment being increased over two-fold from the year before, from 184,000 in 1965 to 385,000 troops in 1966. In 1967, U.S. deployment would top 485,000 and then peak in 1968 with 536,000 soldiers.

Throughout 1967, combat activity in the DMZ consisted of artillery duels, North Vietnamese infiltrations, and firefights along the border. As the North Vietnamese actually used their side of the DMZ as a base to stage their infiltration attacks, in May 1967, the U.S. Marines militarized the southern side of the DMZ, which sparked increased fighting inside the DMZ. Also starting in September 1967 and continuing for many months, North Vietnamese artillery batteries pounded U.S Marine positions near the DMZ, which inflicted heavy casualties on American troops. In response, U.S. aircraft launched bombing attacks on North Vietnamese positions across the DMZ.

In early 1967, North Vietnam began preparing for a massive offensive into South Vietnam. This operation, which later came to be known as the Tet Offensive, would have far-reaching consequences on the outcome of the war. The North Vietnamese plan to launch the Tet Offensive came about when political hardliners in Hanoi succeeded in sidelining the moderates in government. As a result of the hardliners dictating government policies, in July 1967, hundreds of moderates, including government officials and military officers, were purged from the Hanoi government and the Vietnamese Communist Party.

By fall of 1967, North Vietnamese military planners had set the date to launch the Tet Offensive on January 31, 1968. In the invasion plan, the Viet Cong was to carry out the offensive, with North Vietnam only providing weapons and other material support. The Tet Offensive, which was known in North Vietnam as “General Offensive, General Uprising”, called for the Viet Cong to launch simultaneous attacks on many targets across South Vietnam, which would be accompanied with calls to the civilian population to launch a general uprising. North Vietnam believed that a civilian uprising in the south would succeed because of President Thieu’s unpopularity, as evidenced by the constant civil unrest and widespread criticism of government policies. In this scenario, once President Thieu was overthrown, an NLF-led communist government would succeed in power, and pressure the United States to end its involvement in South Vietnam. Faced with the threat of international condemnation, the United States would be forced to acquiesce, and withdraw its forces from Vietnam.