(Taken from Vietnam War – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 5)

As early as 1961, under the top-secret Oplan 34A by the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and later in 1964, under the Military Assistance Command, Vietnam – Studies and Operations Group (MACV-SOG), U.S. Navy fast patrol boats transported South Vietnamese commandos on small attack missions inside North Vietnam. One such mission, which would have far-reaching consequences, occurred on July 30, 1964, when South Vietnamese commandos attacked two North Vietnamese islands in the Gulf of Tonkin. The USS Maddox, an American destroyer operating as an electronic spy ship, was located nearby. On August 2, 1964, the commander of the USS Maddox reported being attacked by three North Vietnamese torpedo boats, but that the attack was thwarted. Two days later, August 4, the USS Maddox, now joined by another electronic spy ship, the USS Turner Joy, again reported being attacked by North Vietnamese torpedo boats.

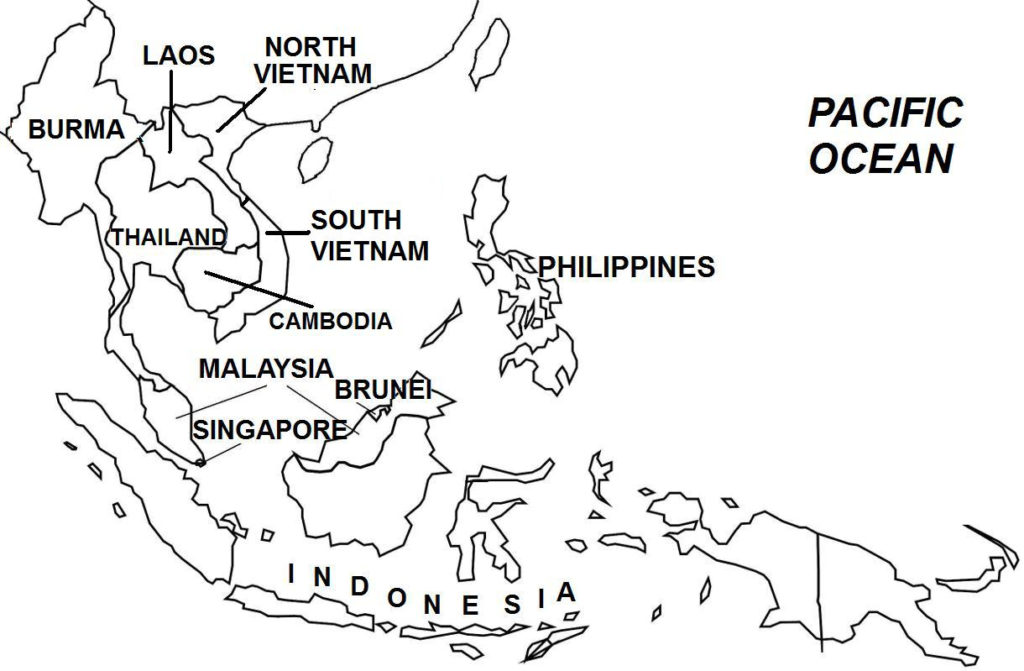

This second incident was later determined to not having occurred. However, after the second “attack”, President Johnson announced to the American public that U.S. naval forces in the Gulf of Tonkin had been attacked by North Vietnam. U.S. President Lyndon B. Johnson then ordered retaliatory air strikes, where U.S. planes struck North Vietnamese naval bases and an oil storage facility. President Johnson also called on the U.S. Congress to pass a resolution that would guarantee “freedom…and peace in Southeast Asia” and support “all necessary action to protect our Armed Forces”.

On August 7, 1964, U.S. Congress overwhelmingly passed the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution (Senate: 88-2 and House of Representatives: 416-0), which came into law on August 10, which gave President Johnson broad powers to use all necessary military force in Southeast Asia in support of its allies there. The Resolution essentially gave President Johnson the authority to go to war against North Vietnam without first obtaining a Declaration of War from U.S. Congress.

The U.S. air strikes, the U.S. spy activities in the Gulf of Tonkin, and the South Vietnamese infiltration missions convinced the Hanoi government that the United States was intervening in the war, and worse, it was planning to invade North Vietnam. As a result, the Ho regime increased military pressure in South Vietnam to overthrow the Saigon government before the United States could intervene. In early 1965, North Vietnamese and Viet Cong forces launched a series of attacks across South Vietnam, with concentrations in the Central Highlands east toward the coast to cut South Vietnam in two, and in the region west of Saigon and near the Cambodian border. U.S. military installations in South Vietnam also were targeted. In November 1964, the Bien Hoa airport, headquarters of the U.S. Air Force command in South Vietnam, was attacked by Viet Cong mortar fire, killing and wounding dozens of American servicemen and damaging several planes. Then in February 1965, Viet Cong units attacked the U.S. air base at Pleiku, Central Highlands, killing 9 U.S. soldiers and wounding 70 others, which was followed three days later, by an explosion that destroyed a hotel at Qui Nohn, killing 23 U.S. soldiers.

As a result of the Viet Cong escalation, President Johnson authorized Operation Rolling Thunder, a limited-scale bombing of North Vietnam, which began on March 2, 1965, with the stated aims of boosting South Vietnamese morale, deterring North Vietnam from supporting the Viet Cong/NLF, and stopping North Vietnamese forces from entering South Vietnam. Initially planned to last only 8 weeks, the bombing campaign became an incremental, sustained effort that lasted 44 months, ending in November 1968. Under Operation Rolling Thunder, President Johnson required that the U.S. military’s list of potential targets be subject to his approval, which generated great consternation among the generals who wanted an all-out, large-scale strategic bombing campaign of North Vietnam. U.S. planes also were only allowed to hit targets (such as road and rail systems, industries, and air defenses) inside a designated radius away from Hanoi and Haiphong, as well as from a buffer zone from the North Vietnam-China border. Some of these restrictions would be lifted later.

The incremental nature of Operation Rolling Thunder allowed North Vietnam enough time to strengthen its air defenses. Thus, by 1968, Hanoi, Haiphong, and other vital centers were bristling with 8,000 Soviet-supplied anti-aircraft guns and 300 surface-to-air missile batteries, supported by 350 radar facilities, as well as scores of Soviet MiG-21 fighter planes and 15,000 Soviet air-defense advisers. In February 1965, the Soviet Union further increased its military support to North Vietnam when an American bombing attack coincided with the visit of Soviet Deputy Premier Alexei Kosygin to Hanoi. Previously, the Soviet government had sought a diplomatic resolution to the Vietnam War (despite providing military support to North Vietnam). Ultimately, by the end of Rolling Thunder, the United States lost over 900 planes, while North Vietnam continued to deliver even larger amounts of weapons to South Vietnam through the Ho Chi Minh Trail.

Throughout the war, the United States launched other aerial operations (Steel Tiger, Tiger Hound, and Commando Hunt) on the Ho Chi Minh Trail to try and stop the flow of men and materiel from North Vietnam to South Vietnam, but all of these ultimately proved unsuccessful.