On August 3, 1959, Portugal’s colonial police force opened fire on striking dock workers in Bissau, the capital of Portuguese Guinea. Dozens of workers were killed. The workers had been incited to strike by the nationalist organization, African Party for the Independence of Guinea and Cape Verde or PAIGC (Portuguese: Partido Africano da Independência da Guiné e Cabo Verde), whose aim was to end Portuguese colonial rule and achieve independence for Guinea and Cape Verde. Initially, the PAIGC wanted to achieve its aims through dialogue and a negotiated settlement with the Portuguese. By the late 1950s, however, the Guinean nationalists had become radicalized and militant.

In March 1962, PAIGC militants in Cape Verde attacked Praia. Other rebel attacks also took place in many parts of Guinea. In June 1963, the rebels attacked government forces in the Guinean towns of Tite, Buba, and Falacunda. By July, rebel activities also were felt in the Guinean northern regions. Earlier in April 1964, the Portuguese had lost control of the Guinean southern coast after the rebels captured Como Islands. Cassaca and Cantanhez also fell to the insurgents.

The sudden outbreak and rapid spread of the insurrection caught the Portuguese by surprise. The Portuguese Army also had just recently transferred some of its Guinean forces to Angola and Mozambique, where other wars for independence had broken out earlier. Consequently, the remaining Portuguese forces in Guinea were undermanned and were reduced to defending the remaining territories still under colonial control.

(Taken from Portuguese Colonial Wars – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 3)

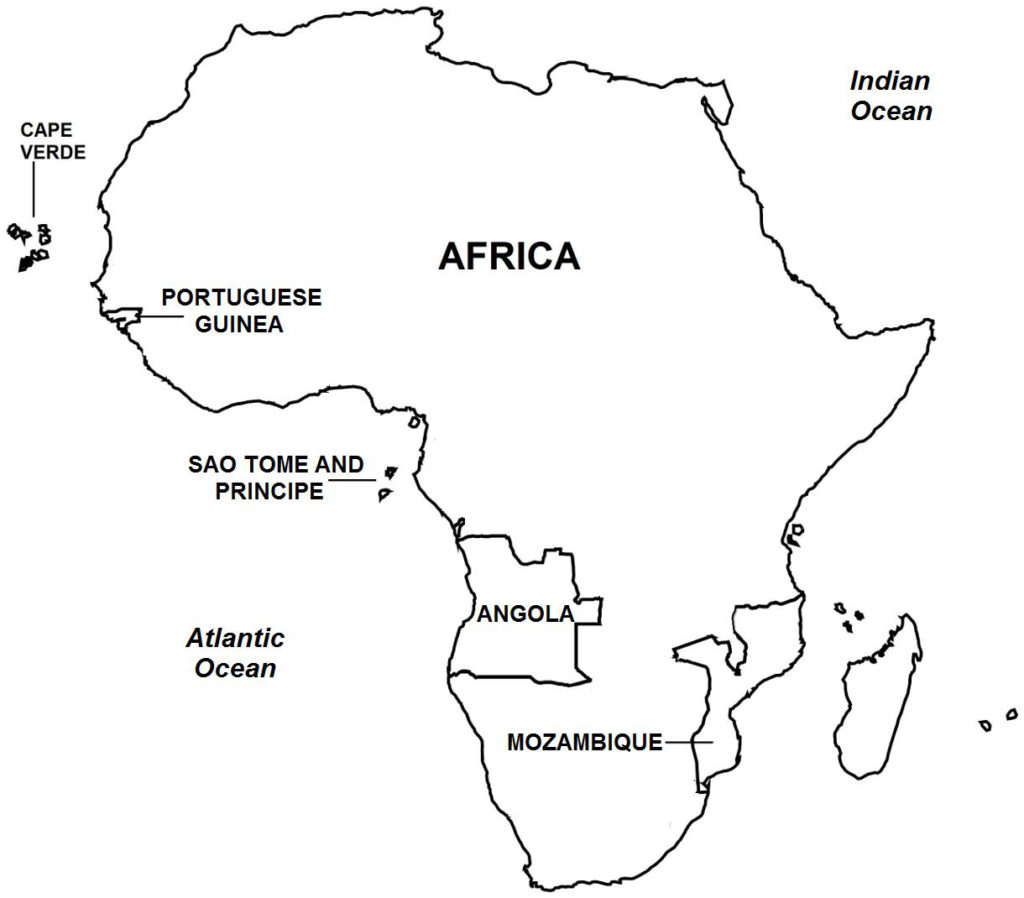

During the colonial era, Portugal’s territorial possessions in Africa consisted of Angola, Mozambique, Portuguese Guinea, Cape Verde, and São Tomé and Príncipe (Map 24). When World War II ended in 1945, a surge of nationalism swept across the various African colonies as independence groups emerged and demanded the end of European colonial rule. As these demands soon intensified into greater agitation and violence, most of the European colonizers relented, and by the 1960s, most of the African colonies had become independent countries.

Bucking the trend, Portugal was determined to hold onto its colonial possessions and went so far as to declare them “overseas provinces”, thereby formally incorporating them into the national territories of the motherland. Nearly all the black African liberation movements in these Portuguese “provinces” turned their attention from trying to gain independence through negotiated settlement to launching insurgencies, thereby starting revolutionary wars. These wars took place through the early 1960s to the first half of the 1970s, and were known collectively as the Portuguese Colonial War, and pitted the Portuguese Armed Forces against the African guerilla militias in Angola, Mozambique, and Portuguese Guinea. At the war’s peak, some 150,000 Portuguese soldiers were deployed in Africa.

By the 1970s, these colonial wars had become extremely unpopular in Portugal, because of the mounting deaths in Portuguese soldiers, the irresolvable nature of the wars through military force, and the fact that the Portuguese government was using up to 40% of the national budget to the wars and thus impinging on the social and economic development of Portuguese society. Furthermore, the wars had isolated Portugal diplomatically, with the United Nations constantly putting pressure on the Portuguese government to decolonize, and most of the international community imposing a weapons embargo and other restrictions on Portugal. In April 1974, dissatisfied officers of the military carried out a coup that deposed the authoritarian regime of Prime Minister Marcelo Caetano. The coup, known as the Carnation Revolution, produced a sudden and dramatic shift in the course of the colonial wars.