On July 5, 1943, the German Army launched Operation Citadel, initiating the Battle of Kursk with the objective of pinching off the Soviet salient. The northern front of the offensive bogged down within four days. On the southern front, the German 4th Panzer Army made slow, steady progress and broke through a series of Soviet defensive lines. On July 12, the Soviets launched their counter-offensives on the northern and southern fronts. In the south, the Soviet 5th Guards Tank Army clashed with units of the German 4th Panzer Army, breaking the German attack before the third defensive line near the town of Prokhorovka.

Also on July 12, Adolf Hitler ordered that Operation Citadel be discontinued, in order to transfer some units to southern Italy where the Western Allies had opened a second front. Following the German failure at the Battle of Kursk, the Soviet Red Army wrested the strategic initiative on the Eastern Front, which it would hold for the rest of the war.

It was long held that the Battle of Prokhorovka was the largest tank battle in history. More recent research has dispelled this myth: only 294 German tanks and 616 Soviet tanks were involved, not the 1,200 to 2,000 tanks previously believed. German losses of 3,500 – 10,000 troops and 350-400 tanks have also been disproved, as more archival records place these at 800 troops and 43-80 tanks. By comparison, Soviet losses at Prkhorovka were 5,500 troops and 300-400 tanks.

(Excerpts taken from Wars of the 20th Century – World War II in Europe)

Preparations for the Battle of Kursk On March 10, 1943, as the battle of Kharkov was winding down, General Manstein, head of German Army Group South, set his sights on eliminating a large gap around Kursk that had formed between his forces and those of German Army Group Center. With Hitler issuing Order No. 5 (March 13) authorizing such an operation, General Manstein and General Gunther von Kluge, commander of German Army Group Center, made preparations to immediately attack the Kursk salient. But with strong Soviet concentrations on the northern side of the salient, as well as reinforcements being rushed to the south to stem General Manstein’s northern advance, the proposed joint offensive was suspended. By then also, German forces were exhausted, and the rasputitsa season had set in, preventing further large-scale armored movement.

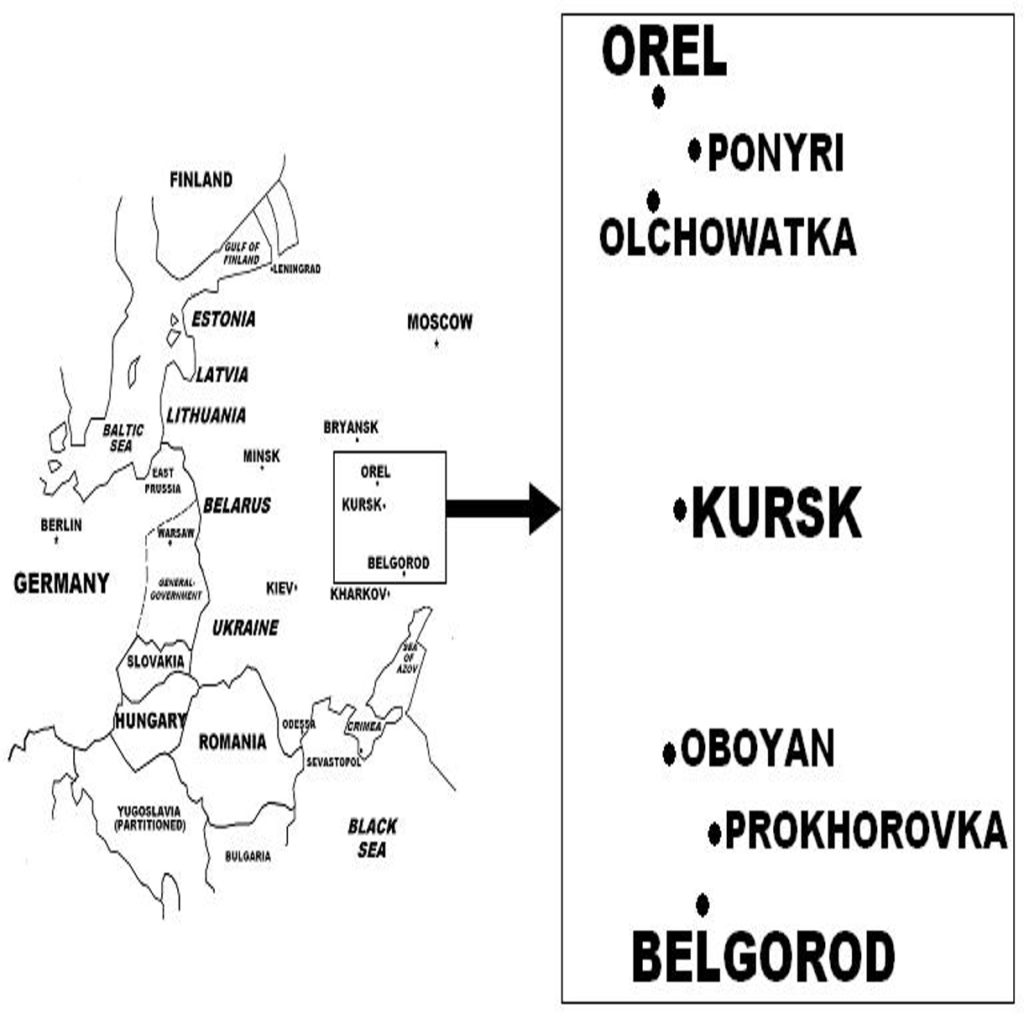

The Kursk salient was a Soviet protrusion into German-occupied territory, measuring 160 miles long from north to south and 100 miles from east to west. Kursk and the surrounding region held no strategic value to either side, but to the Germans (and the Soviets), pinching off the salient would eliminate the danger to their flanks.

In April 1943, Hitler’s Order No. 6 formalized the attack on the Kursk salient under Operation Citadel, which consisted of a pincers movement aimed at trapping five Soviet armies, with the northern pincer of German Army Group Center’s 9th Army thrusting from Orel, and the southern pincer of German Army Group South’s 7th Panzer Army and German Army Detachment Kempf advancing from around Belgorod. The offensive was set for May 3.

In late April 1943, Kluge expressed doubts to Hitler about the feasibility of Operation Citadel, as German air reconnaissance showed that the Soviets were constructing strong fortifications along the northern side of the salient. As well, General Manstein was concerned, as his idea of launching a surprise attack on the unfortified salient could not be achieved anymore. The May 3 launch was not met, and on May 4, Hitler met with Generals Kluge and Manstein and other senior officers to discuss whether or not Operation Citadel should proceed, or that other options be explored. But as the meeting produced no consensus, Hitler remained committed to the operation, resetting its launch for June 12, 1943. With other issues consequently coming up, Hitler postponed the launch date to June 20, then to July 3, and finally to July 5, 1943.

As Operation Citadel was successively pushed back, with the delays ultimately lasting over two months, it also grew in importance, as Hitler saw Kursk as the battle that would restore German superiority in the Eastern Front following the Stalingrad debacle, which continued to weigh heavily on him and the German High Command. Like his generals, Hitler was concerned with the massive Soviet buildup in the salient, but believed that his forces would break through, as well as surprise the enemy, using the Wehrmacht’s latest armored weapons, the versatile Panther tank, the heavy Tiger battle tank, and the goliath Elefant (“Elephant”) tank destroyer. Regaining the military initiative with a victory at Kursk also might convince Hitler’s demoralized Axis partners, Italy, Romania, and Hungary, whose armies were battered at Stalingrad, to reconsider quitting the war.

Hitler’s concerns regarding Kursk were warranted, as the Soviets were indeed fully concentrating on the region. But unbeknown to Hitler and the German senior staff, Stalin and the Soviet High Command were aware of many details of Operation Citadel, with the information being provided to Soviet intelligence by the Lucy spy ring, a network of anti-Nazi German officers working clandestinely in cooperation with the Swiss intelligence bureau. Stalin and a number of senior officers wanted to launch a pre-emptive attack to disrupt the German plans.

However, General Georgy Zhukov, deputy head of the Soviet High Command and who was instrumental in the Soviet successes in Leningrad, Moscow, and Stalingrad and was therefore highly regarded by Stalin, convinced the latter to adopt a strategic defense against the German attack, and then to launch a counter-offensive after the Wehrmacht was weakened. Under General Zhukov’s direction, the Soviet Central Front and Voronezh Front, which defended the northern and southern sides of the salient respectively, implemented a “defense-in-depth” strategy: using 300,000 civilian laborers, six defensive lines (three main forward and three secondary rear lines) were constructed on either side of Kursk, the total depth reaching over 90 miles. These defensive lines, particularly the main forward lines, were fortified with minefields, wire entanglements, anti-tank obstacles, infantry trenches, dug-in armored vehicles, and artillery and machinegun emplacements.

A German attack, even if it broke through all six lines while facing furious Soviet artillery fire in the minefields in between each line, would then encounter additional defensive lines by the reserve Soviet Steppe Front; by then, the Germans would have advanced through many defensive layers a distance of 190 miles under continuous Soviet air and armored counter-attacks and artillery fire.

The buildup to Kursk also saw the Soviets making extensive use of military deception, e.g. dummy airfields, camouflaged artillery positions, night movement of troops, false radio communications, concealed troop concentrations and ammunition stores, spreading rumors in German-held areas, etc. These measures were so effective that the Germans grossly underestimated Soviet strength at Kursk: at the start of the battle, the Red Army had assembled 1.9 million troops, 5,100 tanks, and 25,000 artillery pieces and mortars, while the Germans fielded 780,000 troops, 2,900 tanks, and 10,000 artillery pieces and mortars. This great imbalance of forces, as well as large numbers of Red Army reserves and extensive Soviet defensive preparations, would be decisive in the outcome of the battle.