On July 9, 1900, forty-five Christians, which included men, women, and children, were killed in Taiyuan, Shanxi Province in northern China during the Boxer Rebellion. It was long held that the killings were ordered by Shanxi Province governor Yuxian, who had imposed anti-foreign, anti-Christian policies in the province. More recent research indicates that the massacre resulted from mob violence rather than a direct order from the provincial government. Subsequently, some 2,000 Chinese Christians were killed in Shanxi Province. Also during this time across northern China, Christian missionaries and Chinese parishioners were being targeted for violence by the Boxers as well as by government troops.

(Excerpts taken from Boxer Rebellion – Wars of the 20th Century – Twenty Wars in Asia)

The Boxers In the late 19th century, a secret society called the “Righteous and Harmonious Fists” (Yihequan) was formed in the drought-ravaged hinterland regions of Shandong and Zhili provinces. The sect formed in the villages, had no central leadership, operated in groups of tens to several hundreds of mostly young peasants, and held the belief that China’s problems were a direct consequence of the presence of foreigners, who had brought into the country their alien culture and religion (i.e. Christianity).

Sect members practiced martial arts and gymnastics, and performed mass religious rituals, where they invoked Taoist and Buddhist spirits to take possession of their bodies. They also believed that these rituals would confer on them invincibility to weapons strikes, including bullets. As the sect was anti-foreign and anti-Christian, it soon gained the attention of foreign Christian missionaries, who called the group and its followers “Boxers” in reference to the group’s name and because its members practiced martial arts.

The Qing government, long wary of secret societies which historically had seditious motives, made efforts to suppress the Boxers. In October 1899, government troops and Boxers clashed in the Battle of Senluo Temple in northwest Shandong Province. In this battle, Boxers proclaimed the slogan “Support the Qing, destroy the foreign” which drew the interest of some high-ranking conservative Qing officials who saw that the Boxers were a potential ally against the foreigners. Also by this time, the Boxers had renamed their organization as the “Righteous and Harmonious Militia (Yihetuan)”, using the word “militia” to de-emphasize their origin as a secret society and give the movement a form of legitimacy. Even then, the Qing government continued to view the Boxers with suspicion. In December 1899, the Qing court recalled the Shandong provincial governor, who had shown pro-Boxer sympathy, and replaced him with a military general who launched an anti-Boxer campaign in the province.

The Boxers’ grassroots organizational structure made its suppression difficult. The movement rapidly spread beyond Shandong and Zhili provinces. By April-May 1900, Boxers were operating in large areas of northern China, including Shanxi and Manchuria, and across the North China Plains. The Boxers killed Chinese Christians, burned churches, and looted and destroyed Christian houses and properties. As a result of these attacks, and those perpetrated during the Boxer Rebellion, more than 30,000 Chinese Christians, 130 Protestant missionaries, and 50 Catholic priests and nuns were killed.

The Boxer movement’s decentralized organization was its main strength, as individual units could mobilize and disband at will, and could be transferred quickly to other areas. But its lack of a unified structure and central leadership were also its weakest points, as Boxer units were restricted by a lack of coordination and over-all command. Boxers also suffered from a lack of military training and adequate weapons, and thus fought at a great disadvantage and easily broke apart when the fighting became intense.

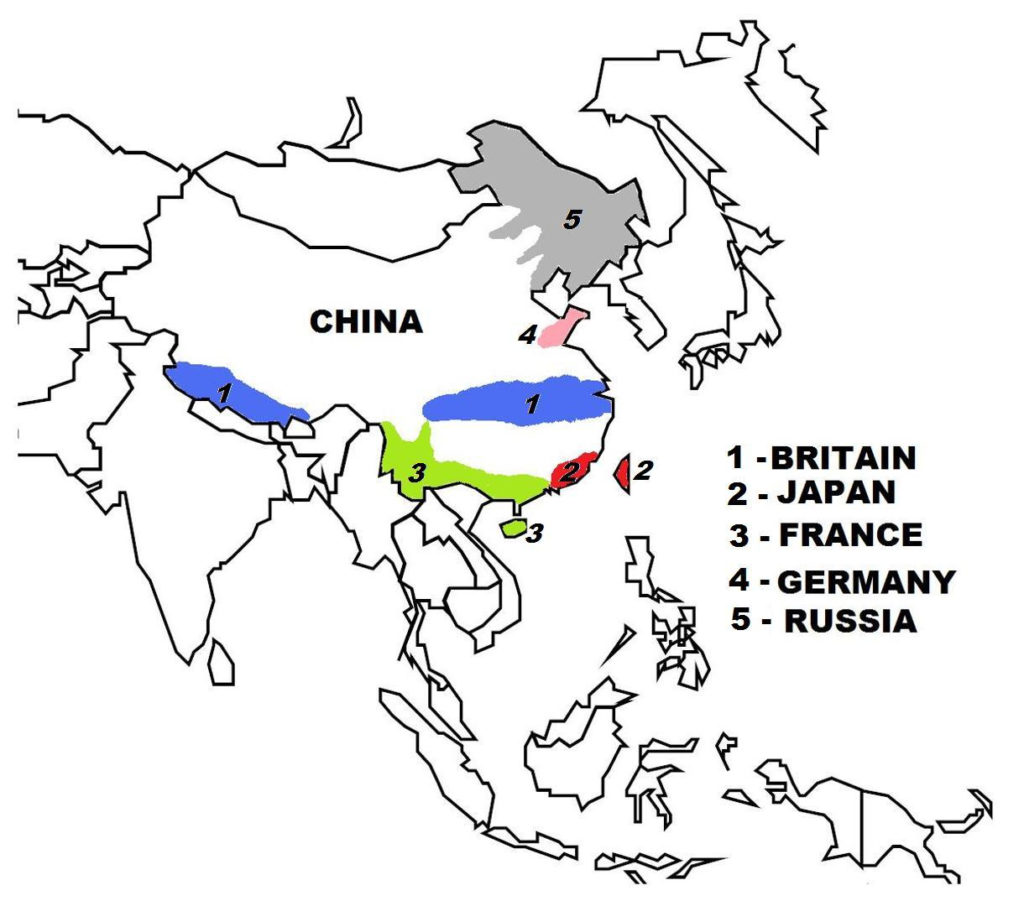

By May 1900, thousands of Boxers were occupying areas around Beijing, including the vital Beijing-Tianjin railway line. They attacked villages, killed local officials, and destroyed government infrastructures. The violence alarmed the foreign diplomatic community in Beijing. The foreign diplomats, their staff, and families in Beijing had their offices and residences located at the Legation Quarter, located south of the city. The Legation Quarter consisted of diplomatic missions from eleven countries: Britain, France, Russia, United States, Germany, Austria-Hungary, Japan, Italy, Belgium, Netherlands, and Spain.

In May 1900, the foreign diplomats asked the Qing government that foreign troops be allowed to be posted at the Legation Quarter, which was denied. Instead, the Chinese government sent Chinese policemen to guard the legations. But the foreign envoys persisted in their request, and on May 30, 1900, the Chinese Foreign Ministry (Zongli Yamen) allowed a small number of foreign troops to be sent to Beijing.

The next day (May 31), some 450 foreign sailors and Marines were landed from ships from eight countries and sent by train from Taku to Beijing. But as the situation in Beijing continued to deteriorate, the foreign diplomats felt that more foreign troops were needed in Beijing. On June 6, 1900, and again on June 8, they sent requests to the Zongli Yamen, with both being turned down. A separate request by the German Minister, Clemens von Ketteler, to allow German troops to take control of the Beijing railway station also was turned down. On June 10, 1900, the Chinese government barred the foreign legations from using the telegraph line that linked to Tianjin. In one of the last transmissions from the Legation Quarter, British Minister Claude MacDonald asked British Vice-Admiral Edward Seymour in Tianjin to send more troops, with the message, “Situation extremely grave; unless arrangements are made for immediate advance to Beijing, it will be too late.” And with the subsequent severing of the telegraph line between Beijing and Kiachta (in Russia) on June 17, 1900, for nearly two months thereafter, the Legation Quarter in Beijing would be cut off from the outside world.

On June 11, 1900, the Japanese diplomat, Sugiyama Akira, was killed by Chinese troops in a Beijing street. Then on June 12 or 13, two Boxers entered the Legation Quarter and were confronted by Ketteler, the German Minister, who drove one away and captured the other; the latter soon was killed under unclear circumstances. Later that day, thousands of Boxers stormed into Beijing and went on a rampage, killing Chinese Christians, burning churches, destroying houses, and looting properties. In the next few days, skirmishes broke out between foreign legation troops, and Boxers with the support of anti-foreigner government units. On June 15, 1900, British and German soldiers dispersed Boxers who attacked a church, and rescued the trapped Christians inside; two days later (June 17), an armed clash broke out between German–British–Austro-Hungarian units and Boxer–anti-foreigner government troops.

The Belgian legation was evacuated, as were those of Austria-Hungary, the Netherlands, and Italy, when they came under Boxer attack. By this time, the Christian missions scattered across Beijing were evacuated, with their clergy and thousands of Chinese Christians taking shelter at the Legation Quarter. Soon, the Legation Quarter was fortified, with soldiers and civilians building barricades, trenches, bunkers, and shelters in preparation for a Boxer attack. Ultimately, in the Legation Quarter were some 400 soldiers, 470 civilians (including 149 women and 79 children), and 2,800 Chinese Christians, all of whom would be besieged in the fighting that followed. At the Northern Cathedral (Beitang) located some three miles from the Legation Quarter, some 40 French and Italian soldiers, 30 foreign Catholic clergy, and 3,200 Chinese Christians also took refuge, turning the area into a defensive fortification which also would come under siege during the conflict.

Meanwhile in Taku, in response to British Minister MacDonald’s plea for more troops to be sent to the Beijing foreign legations, on June 10, Vice-Admiral Seymour scrambled a 2,200-strong multinational force of Navy and Marine units from Britain, Germany, Russia, France, the United States, Japan, Italy, and Austria-Hungary, which departed by train from Tianjin to Beijing. On the first day, Seymour’s force traveled to within 40 miles of Beijing without meeting opposition, despite the presence of Chinese Imperial forces (which had received no orders to resist Seymour’s passage) along the way. Seymour’s force reached Langfang, where the rail tracks had been destroyed by Boxers. Seymour’s troops dispersed the Boxers guarding the area, and work crews started repair work on the rail tracks. Seymour sent out a scouting team further on, which returned saying that more sections of the railroad at An Ting had also been destroyed. Seymour then sent a train back to Tianjin to get more supplies, but the train soon returned, its crew saying that the rail track at Yangcun was now destroyed. Having to fight off a number of Boxer attacks, his provisions running low, realizing the futility of continuing to Beijing, and now feeling trapped on both sides, Seymour called off the expedition and turned the trains back, intending to return to Tianjin.

Elsewhere at this point, the Boxer crisis deteriorated even further. On June 15, 1900, at the Yellow Sea where Alliance ships were on high alert, and were awaiting further developments, allied naval commanders became alarmed when Qing forces began fortifying the Taku Forts at the mouth of the Peiho River, as well as setting mines on the river and torpedo tubes at the forts. For Alliance commanders, these actions threatened to cut off allied communication and supply lines to Tianjin, threatening the foreign enclave at Tianjin and Legation Quarter at Beijing, as well as Seymour’s force. The foreign alliance had had no communication with the Seymour force for several days. Alliance commanders then issued an ultimatum demanding that the Taku Forts be surrendered to them, which the Qing naval command rejected. Early on June 17, 1900, fighting broke out at the Taku Forts, with Alliance forces (except the U.S. command, which chose not to participate) launching a naval and ground assault that seized control of the forts.