On May 1, 1960, a United States U-2 spy plane piloted by Francis Gary Powers was shot over Soviet airspace by a Russian surface-to-air missile. Power’s mission, directed by the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), was to take surveillance photographs on an overflight over central Russia from a base in Pakistan to another base in Norway.

Powers survived by parachuting to the ground where he was arrested by Soviet authorities. The U.S. government of President Dwight D. Eisenhower initially stated that the plane was on a NASA research mission but later admitted that the U-2 was conducting surveillance of Russian territory after the Soviet government produced the captured pilot and evidence of the plane’s wreckage, and more important, the intact surveillance equipment and photographs of Soviet military installations taken during the flight.

Subsequently, Powers was convicted of espionage and sentenced to ten years imprisonment. He did not serve the full sentence but was released in February 1962 on a prisoner exchange “spy swap” agreement between the American and Soviet governments.

Following the 1960 incident, the United States made changes to policy, procedures, and protocols regarding surveillance and reconnaissance missions. Subsequently, the U-2 was used in overflight missions in Cuba when in August 1962, the first evidence of the presence of Soviet nuclear-capable surface-to-air missile (SAM) sites were detected on the island, sparking the Cuban Missile Crisis.

(Excerpts taken from Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 2)

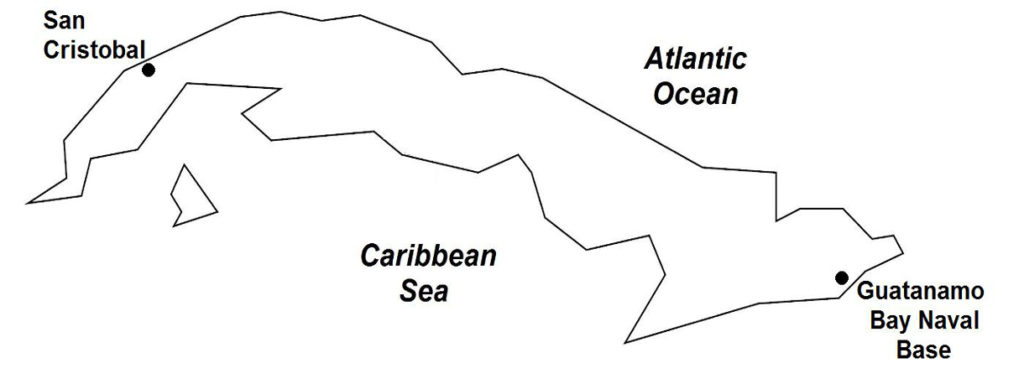

Background of the Cuban Missile Crisis After the unsuccessful Bay of Pigs Invasion in April 1961 (previous article), the United States government under President John F. Kennedy focused on clandestine methods to oust or kill Cuban leader Fidel Castro and/or overthrow Cuba’s communist government. In November 1961, a U.S. covert operation code-named Mongoose was prepared, which aimed at destabilizing Cuba’s political and economic infrastructures through various means, including espionage, sabotage, embargos, and psychological warfare. Starting in March 1962, anti-Castro Cuban exiles in Florida, supported by American operatives, penetrated Cuba undetected and carried out attacks against farmlands and agricultural facilities, oil depots and refineries, and public infrastructures, as well as Cuban ships and foreign vessels operating inside Cuban maritime waters. These actions, together with the United States Armed Forces’ carrying out military exercises in U.S.-friendly Caribbean countries, made Castro believe that the United States was preparing another invasion of Cuba.

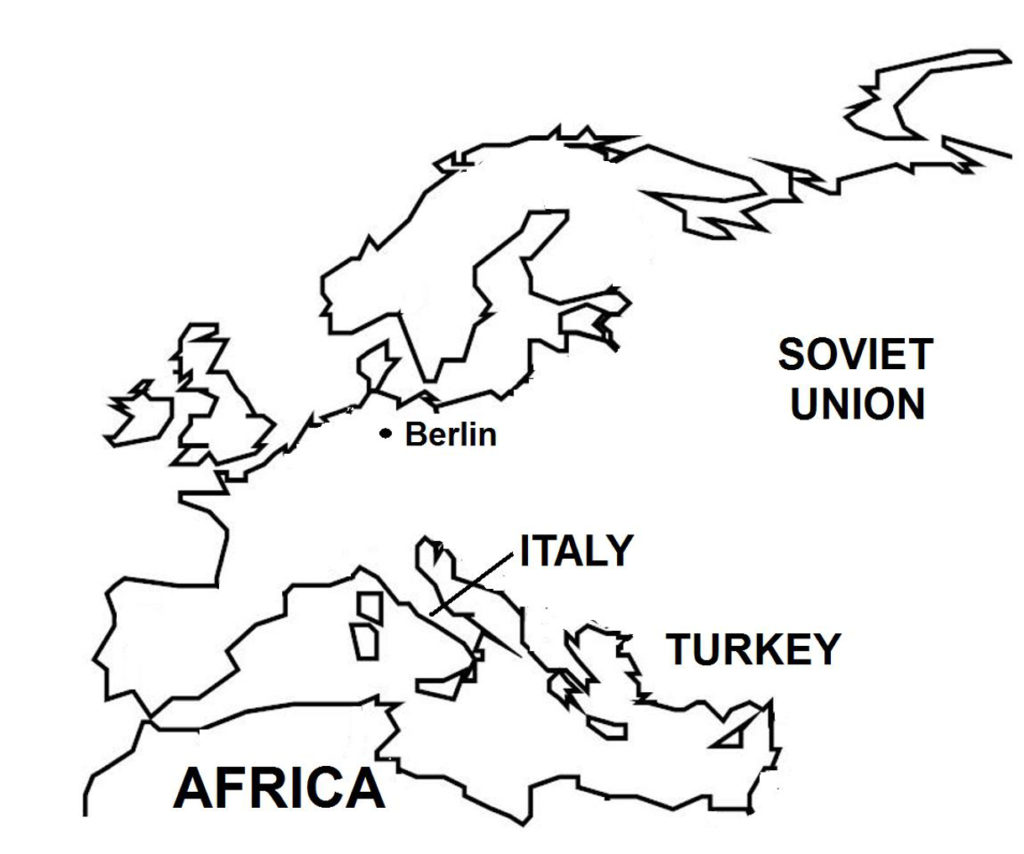

From the time he seized power in Cuba in 1959, Castro had increased the size and strength of his armed forces with weapons provided by the Soviet Union. In Moscow, Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev also believed that an American invasion was imminent, and increased Russian advisers, troops, and weapons to Cuba. Castro’s revolution had provided communism with a toehold in the Western Hemisphere and Premier Khrushchev was determined not to lose this invaluable asset. At the same time, the Soviet leader began to face a security crisis of his own when the United States under the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) installed 300 Jupiter nuclear missiles in Italy in 1961 and 150 missiles in Turkey (Map 33) in April 1962.

In the nuclear arms race between the two superpowers, the United States held a decisive edge over the Soviet Union, both in terms of the number of nuclear missiles (27,000 to 3,600) and in the reliability of the systems required to deliver these weapons. The American advantage was even more pronounced in long-range missiles, called ICBMs (Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles), where the Soviets possessed perhaps no more than a dozen missiles with a poor delivery system in contrast to the United States that had about 170, which when launched from the U.S. mainland could accurately hit specific targets in the Soviet Union.

The Soviet nuclear weapons technology had been focused on the more likely war in Europe and therefore consisted of shorter range missiles, the MRBMs (medium-range ballistic missiles) and IRBMs (intermediate-range ballistic missiles), both of which if installed in Cuba, which was located only 100 miles from southeastern United States, could target portions of the contiguous 48 U.S. States. In one stroke, such a deployment would serve Castro as a powerful deterrent against an American invasion; for the Soviets, they would have invoked their prerogative to install nuclear weapons in a friendly country, just as the Americans had done in Europe. More important, the presence of Soviet nuclear weapons in the Western Hemisphere would radically alter the global nuclear weapons paradigm by posing as a direct threat to the United States.

In April 1962, Premier Khrushchev conceived of such a plan, and felt that the United States would respond to it with no more than a diplomatic protest, and certainly would not take military action. Furthermore, Premier Khrushchev believed that President Kennedy was weak and indecisive, primarily because of the American president’s half-hearted decisions during the failed Bay of Pigs Invasion in April 1961, and President Kennedy’s weak response to the East German-Soviet building of the Berlin Wall in August 1961.

A Soviet delegation sent to Cuba met with Fidel Castro, who gave his consent to Khrushchev’s proposal. Subsequently in July 1962, Cuba and the Soviet Union signed an agreement pertinent to the nuclear arms deployment. The planning and implementation of the project was done in utmost secrecy, with only a few of the top Soviet and Cuban officials being informed. In Cuba, Soviet technical and military teams secretly identified the locations for the nuclear missile sites.

In August 1962, U.S. reconnaissance flights over Cuba detected the presence of powerful Soviet aircraft: 39 MiG-21 fighter aircraft and 22 nuclear weapons-capable Ilyushin Il-28 light bombers. More disturbing was the discovery of the S-75 Dvina surface-to-air missile batteries, which were known to be contingent to the deployment of nuclear missiles. By late August, the U.S. government and Congress had raised the possibility that the Soviets were introducing nuclear missiles in Cuba.

By mid-September, the nuclear missiles had reached Cuba by Soviet vessels that also carried regular cargoes of conventional weapons. About 40,000 Soviet soldiers posing as tourists also arrived to form part of Cuba’s defense for the missiles and against a U.S. invasion. By October 1962, the Soviet Armed Forces in Cuba possessed 1,300 artillery pieces, 700 regular anti-aircraft guns, 350 tanks, and 150 planes.

The process of transporting the missiles overland from Cuban ports to their designated launching sites required using very large trucks, which consequently were spotted by the local residents because the oversized transports, with their loads of canvas-draped long cylindrical objects, had great difficulty maneuvering through Cuban roads. Reports of these sightings soon reached the Cuban exiles in Miami, and through them, the U.S. government.