On June 12, 1948, three European plantation managers were killed by armed militias of the Communist Party of Malaya (CPM). British authorities declared a state of emergency throughout Malaya (now part of modern-day Malaysia), which essentially was a declaration of war against the CPM. What ensued was a twelve-year conflict (1948-1960) that became known as the Malayan Emergency, the British calling it an “emergency” so that business establishments that suffered material losses as a result of the fighting could make insurance claims, which the same would be refused by insurance companies if Malaya were placed under a state of war.

Background On December 7, 1941, with the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, World War II broke out in the Asia-Pacific. Simultaneously, Japan launched an invasion of Southeast Asia. In Malaya, the British government and the CPM formed a tactical alliance, with the British military training over 150 CPM fighters who subsequently formed the core of the anti-Japanese resistance movement. In Europe, Britain itself was fighting for its own survival and consequently was unable to adequately defend Malaya and Singapore, which fell to the Japanese in January-February 1942. Some 130,000 British and other allied troops were taken prisoner.

However, several British soldiers in Malaya who escaped capture retreated to the jungles (some 80% of Malaya was covered in dense mountainous rainforests) where they reorganized as an anti-Japanese resistance group that carried out guerilla operations against the Japanese occupation. Similarly, the CPM, led by its British Army-trained fighters, fled to the jungles, and formed a militia, the Malayan Peoples’ Anti-Japanese Army (MPAJA), which conducted guerilla warfare, attacking Japanese patrols and outposts and sabotaging militarily important infrastructures.

The MPAJA became a large, potent fighting force that spread all across the Malayan Peninsula. It achieved success primarily because it drew great support from the ethnic Chinese population, which was being subjected by the Japanese to severe cruelty. During the war, tens of Chinese were killed by the Japanese, their properties and businesses seized, and hundreds of thousands of others forced to flee from their homes. By contrast, Malayans and ethnic Indians were spared abuse, and Malays in particular were co-opted by the Japanese authorities into carrying out civilian, police and security functions. The Japanese also stoked the nationalist aspirations of Malays, promising them some form of Malayan self-rule.

The pro-British guerilla groups and the MPAJA were tactical allies, but they generally operated separately of each other. By late 1943, a firmer alliance was established between them when the British military, using commandos who infiltrated Malaya and established contact with the MPAJA, promised to provide weapons to the Malayan communist guerillas in exchange for the MPAJA coming under British military authority. The promised weapons were delivered in 1945 as Japanese rule in Malaya was waning, and the MPAJA hid underground some of these arms shipments for future use.

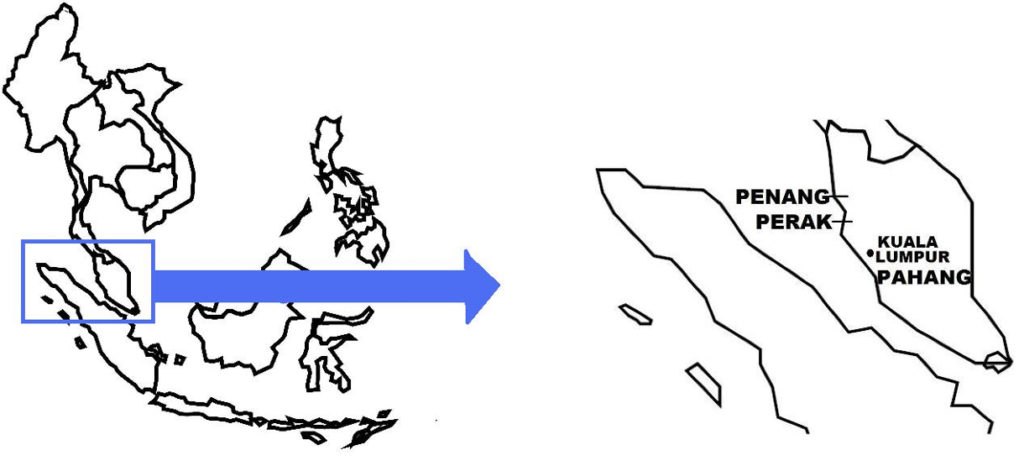

On August 14, 1945, the Asia-Pacific theatre of World War II ended when Japan announced its decision to surrender. A formal ceremony of surrender was made three weeks later, on September 2, 1945. In Malaya, the Japanese Army surrendered to the returning British forces on September 4 (in Penang) and September 13 (in Kuala Lumpur), 1945. On September 12, the British installed a military government, the British Military Administration (BMA), to replace the pre-war civilian colonial government that had administered Malaya. British authorities were hard-pressed to restore normalcy in the immediate post-war period: the Malayan economy was devastated, the tin and rubber industries were inoperational, and poverty and unemployment were rampant. Agricultural infrastructures were export-oriented and not directed toward growing food for the local population, leading to widespread food shortages. Furthermore, banditry, criminality, and a general lawlessness ruled the countryside.

The British recognized the MPAJA’s war-time efforts, leading to joint celebratory parades and the British granting official status to the Malayan communists’ guerilla units. MPAJA fighters were paid a salary and given supplies and provisions. In the post-war period, the MPAJA exacted vengeance on war-time collaborators in the towns and villages. Also in response to the anarchic conditions, hard-line communist elements wanted to overthrow the colonial government, but the MCP leadership decided to cooperate with the British, and acquiesced to an order by the British military to disband MPAJA guerilla units. However, some MPAJA units refused to disband, and although many weapons were turned in, many more were hidden in homes or buried in the ground.

By 1947, the British were making progress in Malaya’s post-war reconstruction: infrastructures were being restored or rebuilt, and the peninsula’s vital tin and rubber industries were rehabilitated. At this time, the CPM operated openly, tacitly tolerated by the British because of their war-time alliance. In March 1947, the CPM came under the leadership of Chin Peng, a hard-line communist who increased anti-British militant actions. Operating through the labor movement (which it controlled), the CPM organized strikes and labor actions aimed at disrupting the Malayan economy, and destabilizing British rule by fomenting local unrest. In this way, it was hoped that a general uprising would follow, leading to the end of British rule and its replacement with a CMP-led communist government. Under CPM instigation, hundreds of strikes were launched, and labor leaders and workers who refused to participate were killed.

War On June 12, 1948, three European plantation managers were killed by armed bands, forcing British authorities to declare a state of emergency throughout Malaya, which essentially was a declaration of war on the CPM. The British called the conflict, which lasted 12 years (1948-1960), an “emergency” so that business establishments that suffered material losses as a result of the fighting, could make insurance claims, which the same would be refused by insurance companies if Malaya were placed under a state of war.

The state of emergency, which was applied first to Perak State (where the murders of the three plantation managers occurred) and then throughout Malaya in July 1948, gave the police authorization to arrest and hold anyone, without the need for the judicial process. In this way, hundreds of CPM cadres were arrested and jailed, and the party itself was outlawed in July 1948. The murders of the three plantation managers are disputed: British authorities blamed the CPM, while Chin Peng denied CPM involvement, arguing that the CPM itself was caught by surprise by the events and was unprepared for war, and that he himself barely avoided arrest in the intensive government crackdown that followed the killings. (Excerpts taken from Wars of the 20th Century: Volume 5 – Twenty Wars in Asia.)