Before the Cambodian Campaign (April– July 1970) began, President Richard Nixon had announced in a nationwide broadcast that he had committed U.S. ground troops to the operation. Within days, large demonstrations of up to 100,000 to 150,000 protesters broke out in the United States, with the unrest again centered in universities and colleges. On May 4, 1970, at Kent State University, Ohio, National Guardsmen opened fire on a crowd of protesters, killing four people and wounding eight others. This incident sparked even wider, increasingly militant and violent protests across the country. Anti-war sentiment already was intense in the United States following news reports in November 1969 of what became known as the My Lai Massacre, where U.S. troops on a search and destroy mission descended on My Lai and My Khe villages and killed between 347 and 504 civilians, including women and children.

(Taken from Vietnam War – Wars of the 20th Century – Twenty Wars in Asia)

Toward the endgame American public outrage further was fueled when in June 1971, the New York Times began publishing the “Pentagon Papers” (officially titled: United States – Vietnam Relations, 1945–1967: A Study Prepared by the Department of Defense), a highly classified study by the U.S. Department of Defense that was leaked to the press. The Pentagon Papers showed that successive past administrations, including those of Presidents Truman, Eisenhower, and Kennedy, but especially of President Johnson, had many times misled the American people regarding U.S. involvement in Vietnam. President Nixon sought legal grounds to stop the document’s publication for national security reasons, but the U.S. Supreme Court subsequently decided in favor of the New York Times and publication continued, and which was also later taken up by the Washington Post and other newspapers.

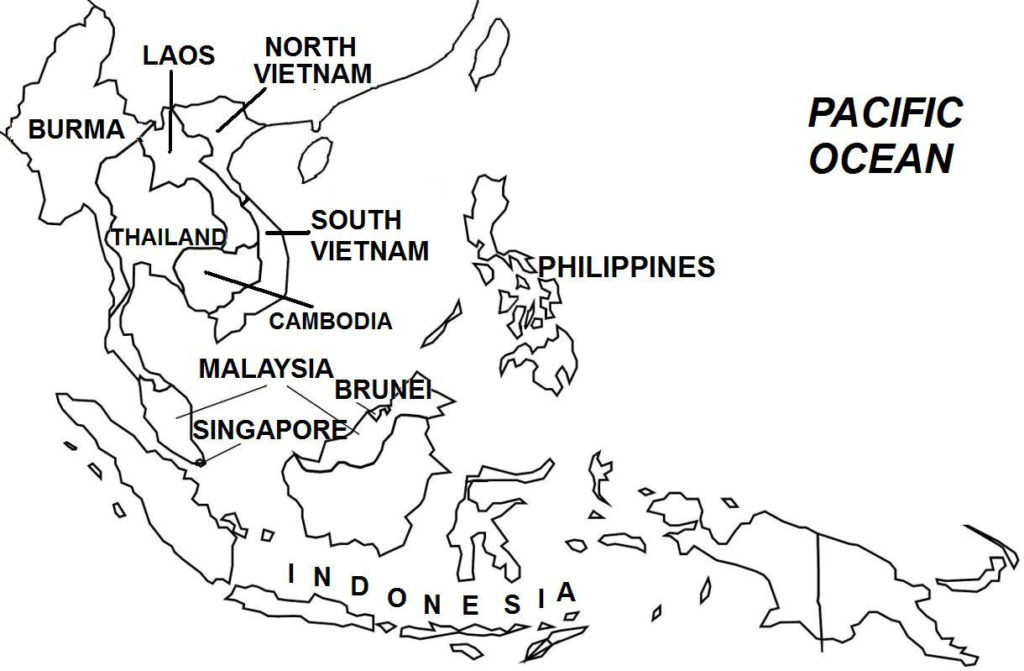

As in Cambodia, the U.S. high command had long desired to launch an offensive into Laos to cut off the logistical portion of the Ho Chi Minh Trail system located there. But restrained by Laos’ official neutrality, the U.S. military instead carried out secret bombing campaigns in eastern Laos and intelligence gathering operations (the latter conducted by the top-secret Military Assistance Command, Vietnam – Studies and Observations Group, MACV-SOG that involved units from Special Forces, Navy SEALS, U.S. Marines, U.S. Air Force, and CIA) there.

The success of the Cambodian Campaign encouraged President Nixon to authorize a similar ground operation into Laos. But as U.S. Congress had prohibited American ground troops from entering Laos, South Vietnamese forces would launch the offensive into Laos with the objective of destroying the Ho Chi Minh Trail, with U.S. forces only playing a supporting role (and remaining within the confines of South Vietnam). The operation also would gauge the combat capability of the South Vietnamese Army in the ongoing Vietnamization program.

In February-March 1971, about 17,000 troops of the South Vietnamese Army, (some of whom were transported by U.S. helicopters in the largest air assault operation of the war), and supported by U.S. air and artillery firepower, launched Operation Lam Son 719 into southeastern Laos. At their furthest extent, the South Vietnamese seized and briefly held Tchepone village, a strategic logistical hub of the Ho Chi Minh Trail located 25 miles west of the South Vietnamese border. The main South Vietnamese column was stopped by heavy enemy resistance and poor road conditions at A Luoi, some 15 miles from the border. North Vietnamese forces, initially distracted by U.S. diversionary attacks elsewhere, soon assembled 50,000 troops against the South Vietnamese, and counterattacked. North Vietnamese artillery particularly was devastating, knocking out several South Vietnamese firebases, while intense anti-aircraft fire disrupted U.S. air transport operations. By early March 1971, the attack was called off, and with the North Vietnamese intensifying their artillery bombardment, the South Vietnamese withdrawal turned into a chaotic retreat and a desperate struggle for survival. The operation was a debacle, with the South Vietnamese losing up to 8,000 soldiers killed, 60% of their tanks, 50% of their armored carriers, and dozens of artillery pieces; North Vietnamese casualties were 2,000 killed. American planes were sent to destroy abandoned South Vietnamese armor, transports, and equipment to prevent their capture by the enemy. U.S. air losses were substantial: 84 planes destroyed and 430 damaged and 168 helicopters destroyed and 618 damaged.

Buoyed by this success, in March 1972, North Vietnam launched the Nguyen Hue Offensive (called the Easter Offensive in the West), its first full-scale offensive into South Vietnam, using 300,000 troops and 300 tanks and armored vehicles. By this time, South Vietnamese forces carried practically all of the fighting, as fewer than 10,000 U.S. troops remained in South Vietnam, and who were soon scheduled to leave. North Vietnamese forces advanced along three fronts. In the northern front, the North Vietnamese attacked through the DMZ, and captured the northern provinces, and threatened Hue and Da Nang. In late June 1972, a South Vietnamese counterattack, supported by U.S. air firepower, including B-52 bombers, recaptured most of the occupied territory, including Quang Tri, near the northern border. In the Central Highlands front, the North Vietnamese objective to advance right through to coastal Qui Nhon and split South Vietnam in two, failed to break through to Kontum and was pushed back. In the southern front, North Vietnamese forces that advanced from the Cambodian border took Tay Ninh and Loc Ninh, but were repulsed at An Loc because of strong South Vietnamese resistance and massive U.S. air firepower.

To further break up the North Vietnamese offensive, in April 1972, U.S. planes including B-52 bombers under Operation Freedom Train, launched bombing attacks mostly between the 17th and 19th parallels in North Vietnam, targeting military installations, air defense systems, power plants and industrial sites, supply depots, fuel storage facilities, and roads, bridges, and railroad tracks. In May 1972, the bombing attack was stepped up with Operation Linebacker, where American planes now attacked targets across North Vietnam. A few days earlier, U.S. planes air-dropped thousands of naval mines off the North Vietnamese coast, sealing off North Vietnam from sea traffic.

At the end of the Easter Offensive in October 1972, North Vietnamese losses included up to 130,000 soldiers killed, missing, or wounded and 700 tanks destroyed. However, North Vietnamese forces succeeded in capturing and holding about 50% of the territories of South Vietnam’s northern provinces of Quang Tri, Thua Thien, Quang Nam, and Quang Tin, as well as the western edges of II Corps and III Corps. But the immense destruction caused by U.S. bombing in North Vietnam forced the latter to agree to make concessions at the Paris peace talks.

At the height of North Vietnam’s Easter Offensive, the Cold War took a dramatic turn when in February 1972, President Nixon visited China and met with Chairman Mao Zedong. Then in May 1972, President Nixon also visited the Soviet Union and met with General Secretary Leonid Brezhnev and other Soviet leaders. A period of superpower détente followed. China and the Soviet Union, desiring to maintain their newly established friendly relations with the United States, aside from issuing diplomatic protests, were not overly provoked by the massive U.S. bombing of North Vietnam. Even then, the two communist powers stood by their North Vietnamese ally and continued to send large amounts of military support.

Since it began in May 1968, the peace talks in Paris had made little progress. Negotiations were held at the main conference hall. However, since February 1970, U.S. National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger and North Vietnamese negotiator Le Duc Tho had been holding secret talks separate from the main negotiations. These secret talks achieved a breakthrough on October 17, 1972 (ten days after the U.S. bombings had forced North Vietnam to return to negotiations), when Kissinger announced that “peace is at hand” and that a mutually agreed draft of a peace agreement was to be signed on October 31, 1972.

However, South Vietnamese President Thieu, when presented with the peace proposal, refused to agree to it, and instead demanded 129 changes to the draft agreement, including that the DMZ be recognized as the international border of a fully sovereign, independent South Vietnam, and that North Vietnam withdraw its forces from occupied territories in South Vietnam. On November 1972, Kissinger presented Tho with a revised draft incorporating South Vietnam’s demands as well as changes proposed by President Nixon. This time, the North Vietnamese government was infuriated and believed it had been deceived by Kissinger. On October 26, 1972, North Vietnam broadcast details of the document. In December 1972, talks resumed which went nowhere, and soon broke down on December 14, 1972.

Also on December 14, 1972, the U.S. government issued a 72-hour ultimatum to North Vietnam to return to negotiations. On the same day, U.S. planes air-dropped naval mines off the North Vietnamese waters, again sealing off the coast to sea traffic. Then on President Nixon’s orders to use “maximum effort…maximum destruction”, on December 18-29, 1972, U.S. B-52 bombers and other aircraft under Operation Linebacker II, launched massive bombing attacks on targets in North Vietnam, including Hanoi and Haiphong, hitting airfields, air defense systems, naval bases, and other military facilities, industrial complexes and supply depots, and transport facilities. As many of the restrictions from previous air campaigns were lifted, the round-the-clock bombing attacks destroyed North Vietnam’s war-related logistical and support capabilities. Several B-52s were shot down in the first days of the operation, but changes to attack methods and the use of electronic and mechanical countermeasures greatly reduced air losses. By the end of the bombing campaign, few targets of military value remained in North Vietnam, enemy anti-aircraft guns had been silenced, and North Vietnam was forced to return to negotiations. On January 15, 1973, President Nixon ended the bombing operations.

One week later, on January 23, negotiations resumed, leading four days later, on January 27, 1973, to the signing by representatives from North Vietnam, South Vietnam, the Viet Cong/NLF through its Provisional Revolutionary Government (PRG), and the United States of the Paris Peace Accords (officially titled: “Agreement on Ending the War and Restoring Peace in Vietnam”), which (ostensibly) marked the end of the war. The Accords stipulated a ceasefire; the release and exchange of prisoners of war; the withdrawal of all American and other non-Vietnamese troops from Vietnam within 60 days; for South Vietnam: a political settlement between the government and the PRG to determine the country’s political future; and for Vietnam: a gradual, peaceful reunification of North Vietnam and South Vietnam. As in the 1954 Geneva Accords (which ended the First Indochina War), the DMZ did not constitute a political/territorial border. Furthermore, the 200,000 North Vietnamese troops occupying territories in South Vietnam were allowed to remain in place.

To assuage South Vietnam’s concerns regarding the last two points, on March 15, 1973, President Nixon assured President Thieu of direct U.S. military air intervention in case North Vietnam violated the Accords. Furthermore, just before the Accords came into effect, the United States delivered a large amount of military hardware and financial assistance to South Vietnam.

By March 29, 1973, nearly all American and other allied troops had departed, and only a small contingent of U.S. Marines and advisors remained. A peacekeeping force, called the International Commission of Control and Supervision (ICCS), arrived in South Vietnam to monitor and enforce the Accords’ provisions. But as large-scale fighting restarted soon thereafter, the ICCS became powerless and failed to achieve its objectives.

For the United States, the Paris Peace Accords meant the end of the war, a view that was not shared by the other belligerents, as fighting resumed, with the ICCS recording 18,000 ceasefire violations between January-July 1973. President Nixon had also compelled President Thieu to agree to the Paris Peace Accords under threat that the United States would end all military and financial aid to South Vietnam, and that the U.S. government would sign the Accords even without South Vietnam’s concurrence. Ostensibly, President Nixon could fulfill his promise of continuing to provide military support to South Vietnam, as he had been re-elected in a landslide victory in the recently concluded November 1972 presidential election. However, U.S. Congress, which was now dominated by anti-war legislators, did not bode well for South Vietnam. In June 1973, U.S. Congress passed legislation that prohibited U.S. combat activities in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia, without prior legislative approval. Also that year, U.S. Congress cut military assistance to South Vietnam by 50%. Despite the clear shift in U.S. policy, South Vietnam continued to believe the U.S. government would keep its commitment to provide military assistance.