With Jaguajay’s fall and the voluntary capitulation of the military garrisons at Caibarien and Cienfuegos three days earlier, Che Guevara proceeded unopposed to Santa Clara. Fighting in the city began in the early morning of December 31, 1958, with confused skirmishes breaking out across the city. From Havana, President Fulgencio Batista dispatched a 22-car armored train containing troop reinforcements, weapons, equipment, and food supplies. Che Guevara’s forces, which had set up blockades around Santa Clara, destroyed the rail tracks and then ambushed the train. The rebels forced the surrender of the reinforcing troops and seized the trains’ cargo. By the afternoon of December 31, Santa Clara’s garrison of 6,500 soldiers, which generally had shown half-hearted performance in battle, surrendered to the rebels.

When reports of the fall of Santa Clara reached Havana, President Batista decided to step down from office, and prepared to leave immediately. A few weeks earlier, in early December, his government had received a major diplomatic setback when the United States ceased recognition of his presidency and urged him to step down as Cuba’s leader. In the early hours of January 1, 1959, Batista and a large entourage of his closest supporters, left Havana for exile in the nearby Dominican Republic. He brought with him a vast amount of money, estimated at $300 million. Batista eventually settled in Portugal, where he was granted political asylum.

Before leaving, Batista had tasked General Cantillo with forming a new civilian government under Supreme Court justice Carlos Piedra. On January 2, the Cuban Supreme Court struck down Justice Piedra’s attempt to take over as president; at the same time, the justices affirmed former Justice Manuel Urrutia, who had been chosen as provisional president by Fidel Castro, as Cuba’s new head of state. General Cantillo tried to form a military government under Colonel Ramon Barquin, a respected public figure who had led an unsuccessful coup against President Batista in 1955. The strength and popularity of Castro’s revolution were overpowering, however, forcing Colonel Barquin to abandon plans to take control of the Cuban Armed Forces in a desperate attempt to prevent Castro from taking power. On January 2, 1959, Che Guevara and Camilo Cienfuego, together with their forces, entered Havana, where large crowds welcomed them as liberators.

(Taken from Cuban Revolution – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 2)

Aftermath of the Cuban Revolution In Havana, President Manuel Urrutia (who Castro had appointed as provisional president and Cuba’s new head of state), and especially Che Guevara, Camilo Cienfuegos, and the M-26-7 fighters, took control of civilian and military institutions of the government. Similarly in Oriente Province, Fidel Castro established authority over the regional governmental and military functions. In the following days, other regional military units all across Cuba surrendered their jurisdictions to rebel forces that arrived. Then from Santiago de Cuba, Fidel Castro began a nearly week-long journey to Havana, stopping at every town and city to large crowds and giving speeches, interviews, and press conferences. On January 8, 1959, he arrived in Havana and declared himself the “Representative of the Rebel Armed Forces of the Presidency”, that is, he was effectively head of the Cuban Armed Forces under the government of President Urrutia and newly installed Prime Minister Jose Miro. Real power, however, remained with Castro.

In the next few months, the Castro regime consolidated power by executing or jailing hundreds of Batista supporters for “war crimes” and relegating to the sidelines the other rebel groups that had taken part in the revolution. During the war, Fidel Castro had promised the return of democracy by instituting multi-party politics and holding free elections. Now however, he spurned these promises, declaring that the electoral process was socially regressive and benefited only the wealthy elite.

Castro denied being a communist, the most widely publicized declaration being during his personal visit to the United States in April 1959, or four months after he gained power. Members of the Popular Socialist Party, or PSP (Cuban communists), however, soon began to dominate key government positions, and Cuba’s foreign policy moved toward establishing diplomatic relations with the Soviet Union and other Eastern Bloc countries. (By 1961 when Castro had declared Cuba a communist state, his M-26-7 Movement had formed an alliance with the PSP, the 13th of March Movement – DR, and other leftist organizations; this coalition ultimately gave rise to the Cuban Communist Party.)

President Urrutia, who was a political moderate and a non-communist, made known his concern about the socialist direction of the government, which put him directly in Castro’s way. Consequently in July 1959, President Urrutia was forced to resign from office, as Prime Minister Miro had done earlier in February. A Cuban communist took over as the new president, subservient to the dictates of Fidel Castro. Castro had become the “Maximum Leader” (Spanish: Maximo Lider), or absolute dictator; he abolished Congress, ruled by decree, and suppressed all forms of opposition. Free speech was silenced, as were the print and broadcast media, which were placed under government control. In the villages, towns, and cities across Cuba, neighborhood watches called the “Committees for the Defense of the Revolution” were formed to monitor the activities of all residents within their jurisdictions and to weed out dissidents, enemies, and “counter-revolutionaries”. In 1959, land reform was implemented in Cuba; private and corporate lands were seized, partitioned, and distributed to peasants and landless farmers.

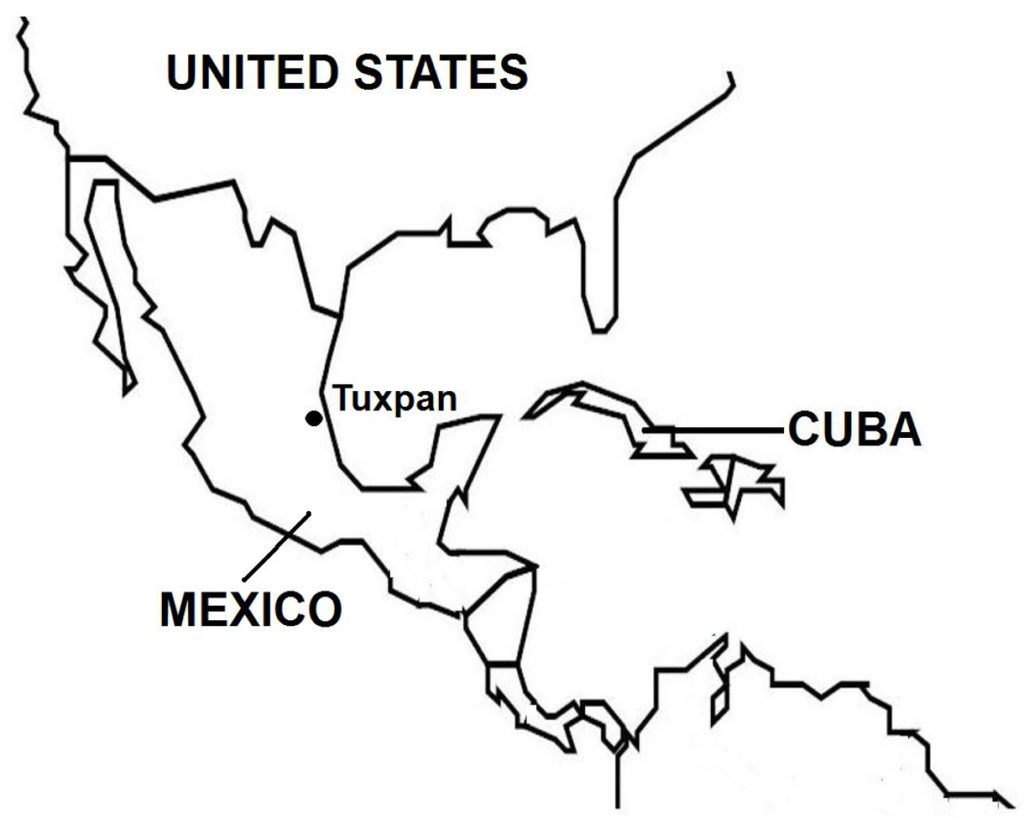

On January 7, 1959, just a few days after the Cuban Revolution ended, the United States recognized the new Cuban government under President Urrutia. But as Castro later gained absolute power and his government gradually turned socialist, relations between the two countries deteriorated rapidly. By July 1959, just seven months later, U.S. president Dwight Eisenhower was planning Castro’s overthrow; subsequently in March 1960, he ordered the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) to organize and train U.S.-based Cuban exiles for an invasion of Cuba.

In 1960, Castro entered into a trade agreement with the Soviet Union that included purchasing Russian oil. Then when U.S. petroleum companies in Cuba refused to refine the imported Russian oil, a succession of measures and retaliatory counter-measures followed quickly. In July 1960, Cuba seized the American oil companies and nationalized them the next month. In October 1960, the United States imposed an economic embargo on Cuba and banned all imports (which constituted 90% of all Cuban exports) from Cuba. The restriction included sugar, which was Cuba’s biggest source of revenue. In January 1960, the United States ended all official diplomatic relations with Cuba, closed its embassy in Havana, and banned trade to and forbid American private and business transactions with the island country.

With Cuba shedding off democracy and taking on a clearly communist state policy, thousands of Cubans from the upper and middle classes, including politicians, top government officials, businessmen, doctors, lawyers, and many other professionals fled the country for exile in other countries, particularly in the United States. However, many other anti-Castro Cubans chose to remain and subsequently organized into armed groups to start a counter-revolution in the Escambray Mountains; these rebel groups’ activities laid the groundwork for Cuba’s next internal conflict, the “War against the Bandits”.